|

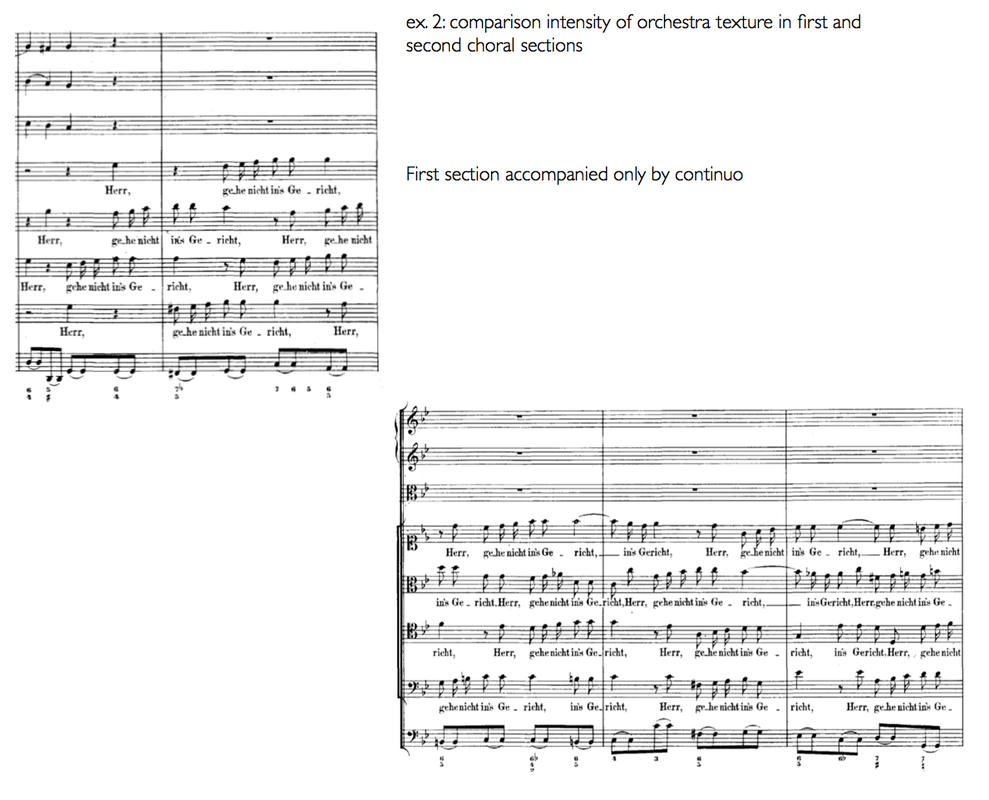

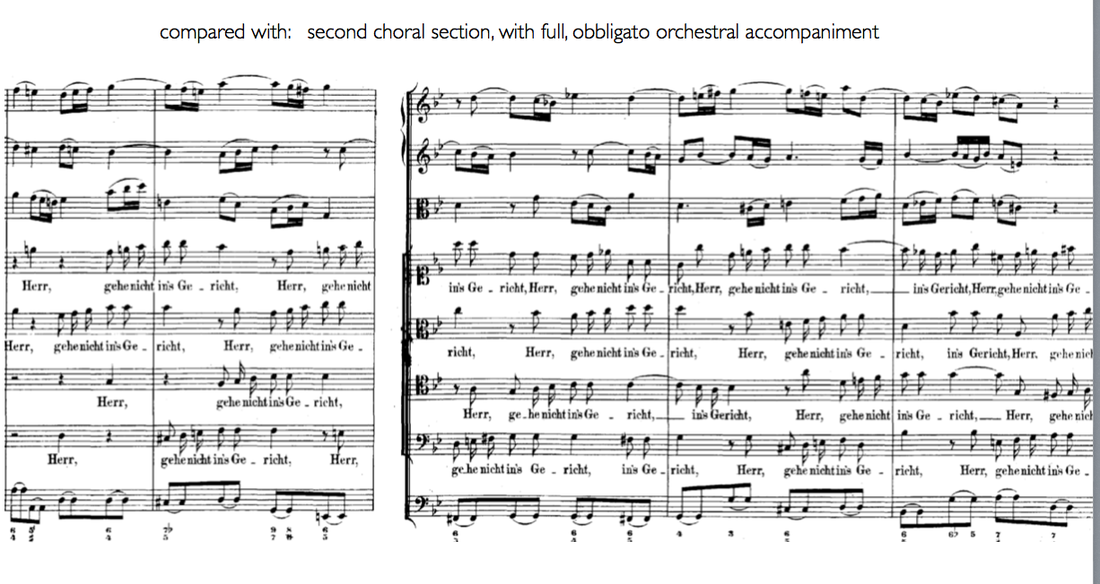

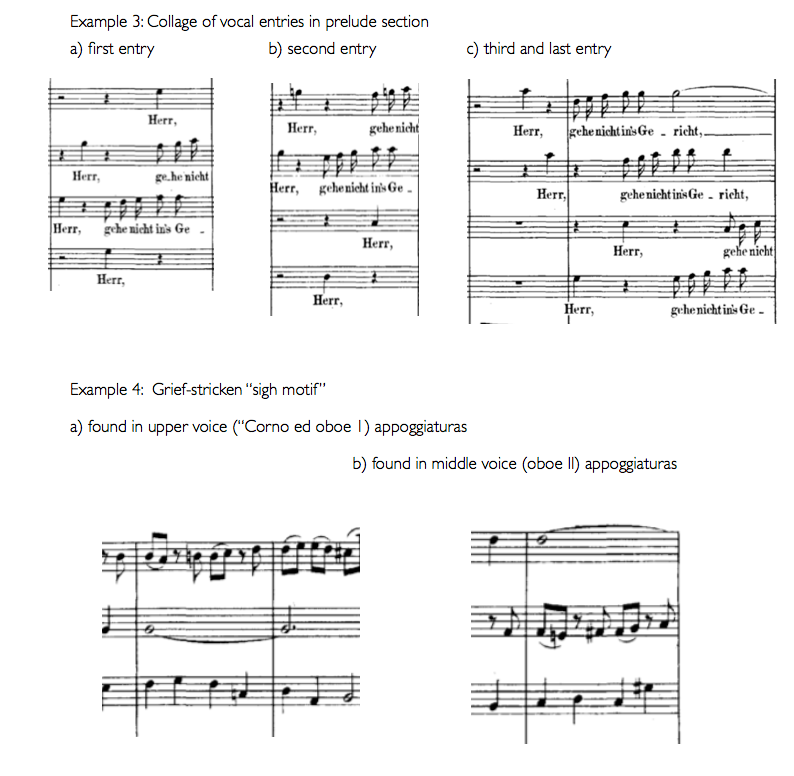

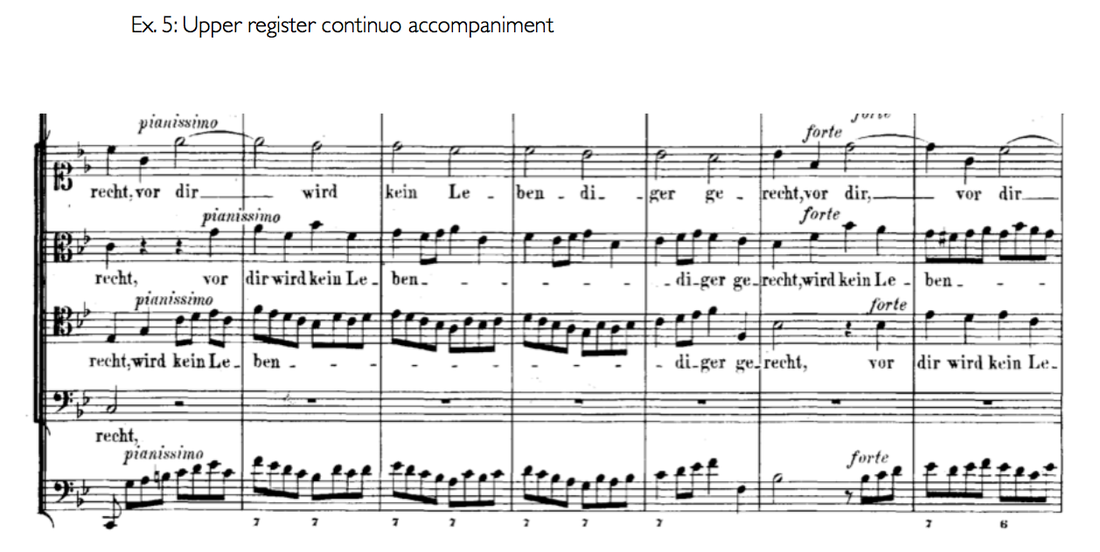

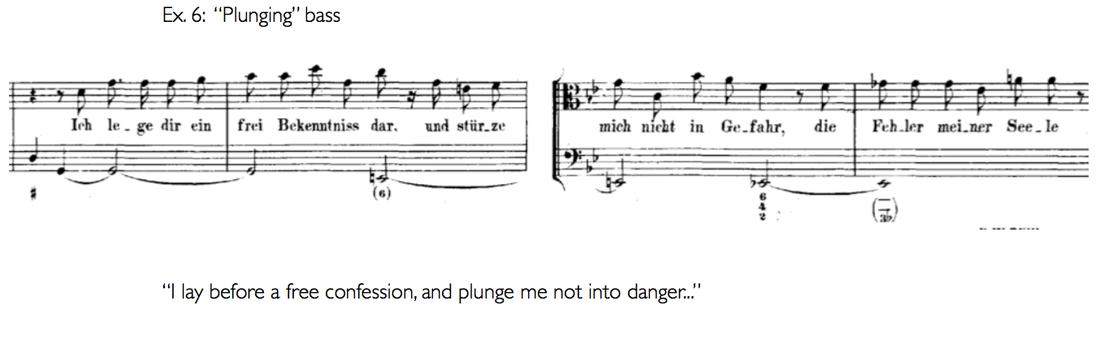

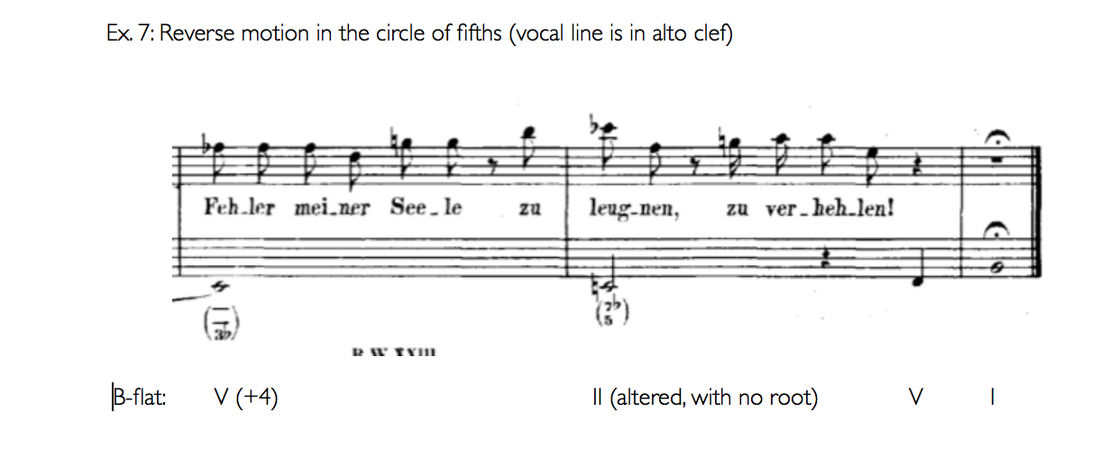

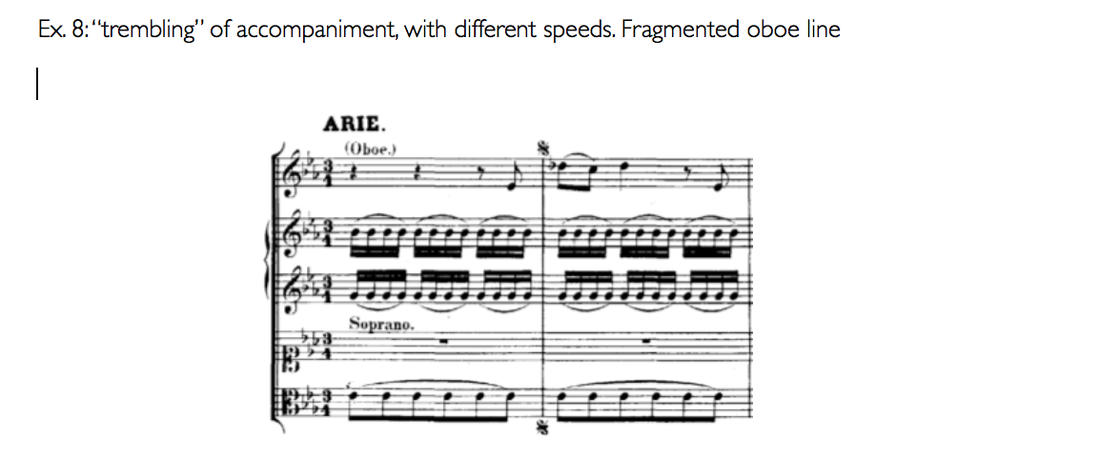

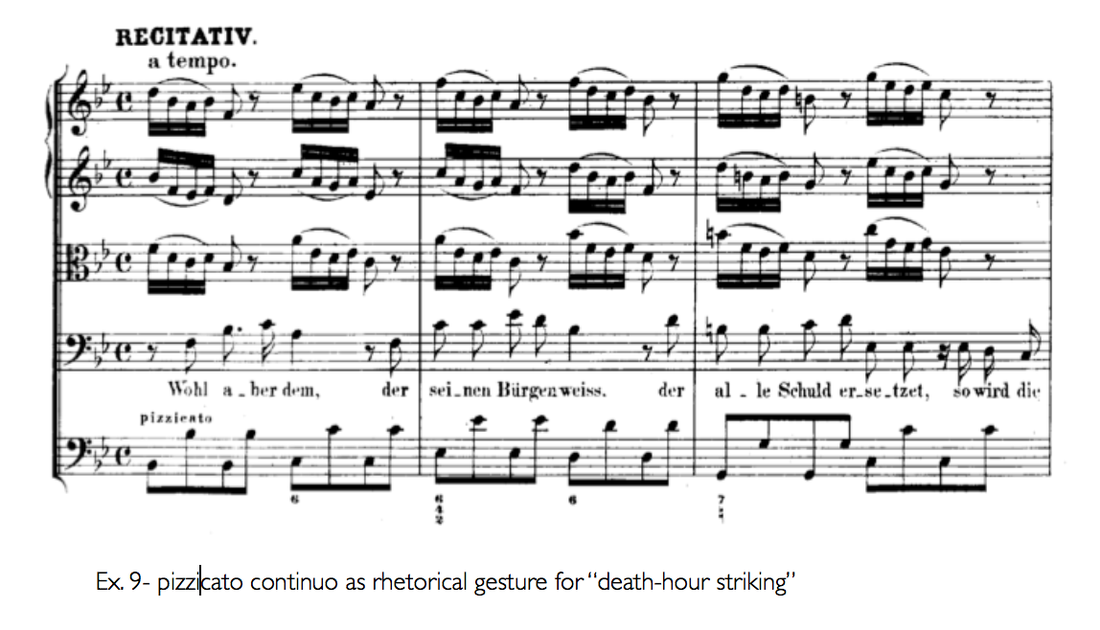

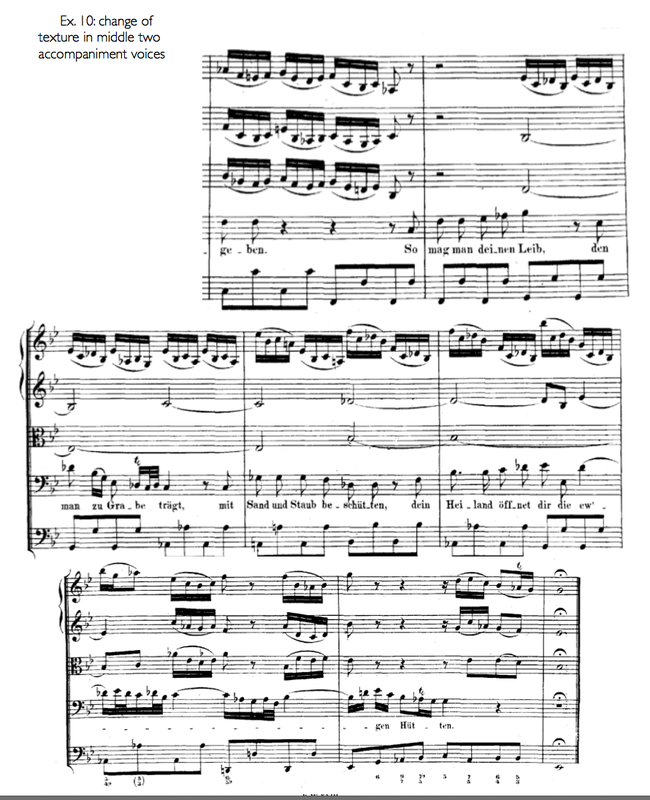

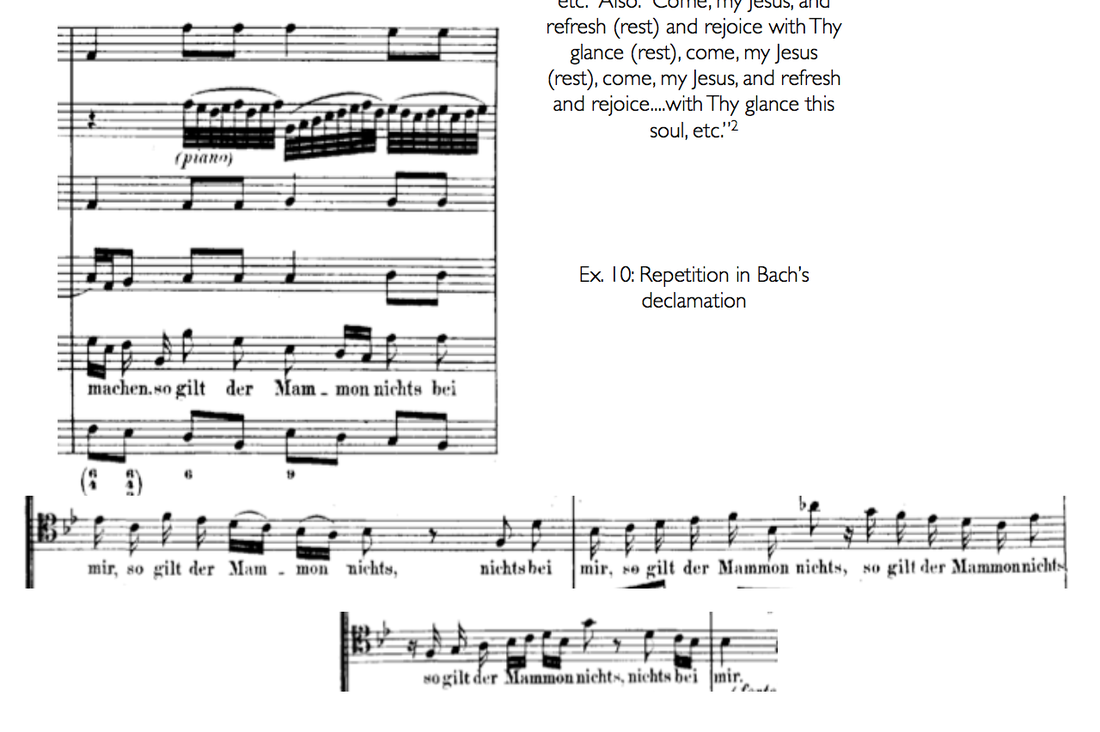

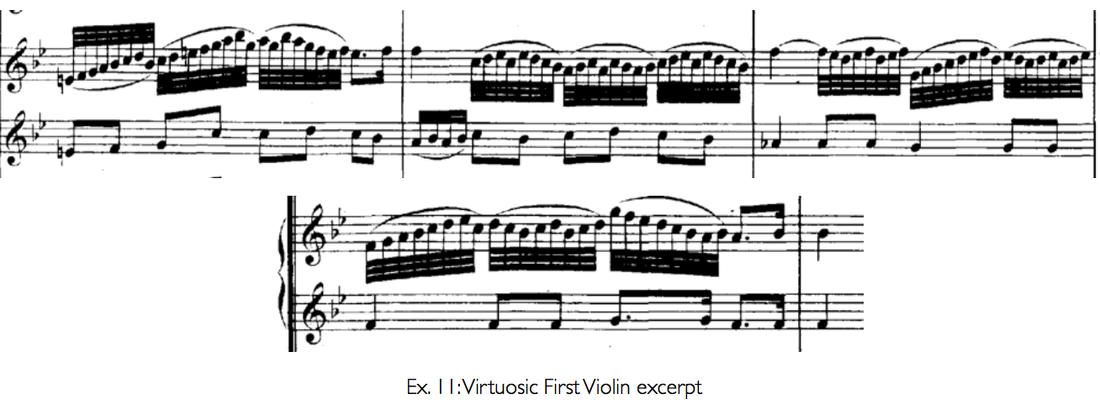

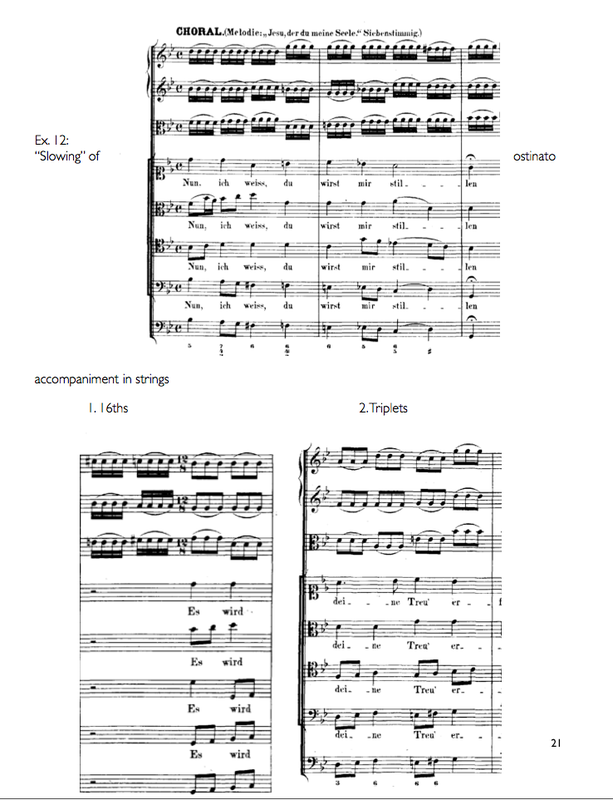

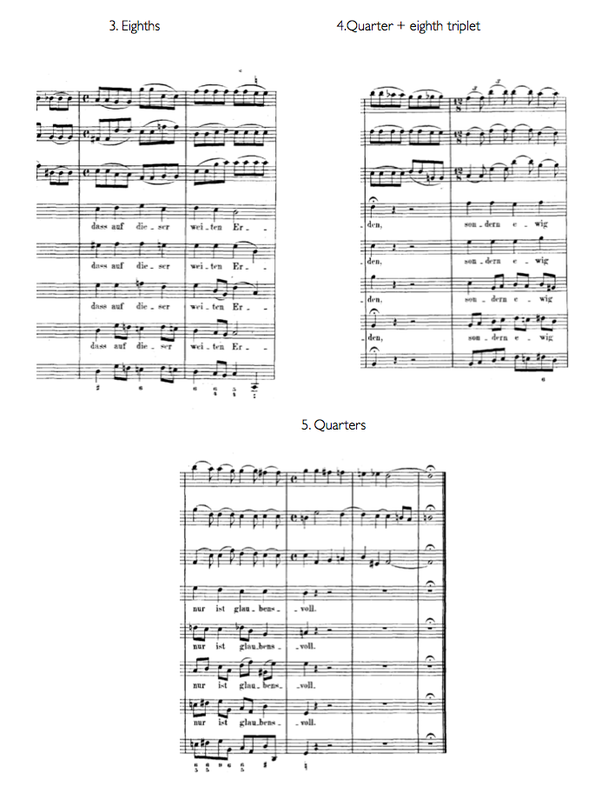

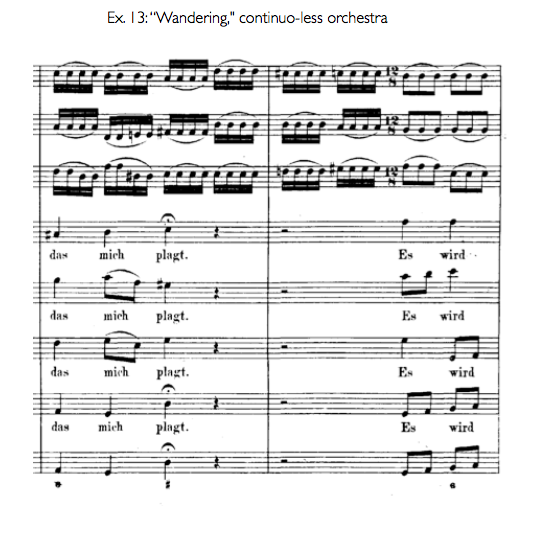

My experience with this cantata first came about when I was to give a short introductory lecture on Bach’s Leipzig cantatas for a class in Fall of 2009. When looking into a heightened use of rhetorical gestures which accompanied Bach’s employment in what would be his home for the remainder of his life, one text pointed to the third movement of this cantata. While I had hitherto been without much experience in the realm of Bach's cantatas, and had little knowledge of the composer’s use of cantata word-painting in his pre-Leipzig days, this movement, a soprano aria, had a profound effect on me. Furthermore, I had enjoyed the large-scale detective work which was carried out earlier in the year for one of J.S. Bach’s motets and which had served as a primer for a new and interesting kind of analysis for me. I was determined to be able to discover on my own the same kind of eye-opening revelations which were so readily exposed in that motet-- to delve into the text, learn about the circumstances of composition, and to see what role this piece played in Bach’s life. In the following analysis, I hope to provide the reader with my own rudimentary revelations about this cantata, number 105, “Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht." The music is oftentimes moving, even to those without a translation of the text or knowledge of the harmonic action involved-- it is my intention to explain not only why this music is so captivating but also to unearth as many of Bach’s hidden devices, found only in study of the score. To accomplish these tasks, I will explore the substantive bulk of the work, discussing matters such as structure and harmony, texture and word-painting. This sort of analyzation requires examination at several levels: first, the work will be seen as a continuous entity and then, as individual movements before I move on to even greater magnification. By providing visual aids to my discussion, I wish to instruct the reader on how Bach arrived at such a solid and effective composition. The cantata, “Herr, gehe nichts in Gerichte," BWV 105 was written shortly after Bach gained control of the St. Thomas cantorate in the spring of 1723. After his move to Leipzig, he was finally able to realize his long time and “ultimate” goal, first expressed fifteen years prior, of establishing a “regulated church music.” Bach’s goal was an ambitious one: he planned on writing a cantata--a multi-movement concert piece--for every Sunday of the church calendar, excepting some Sundays, like those found in the Lenten period (though, it should be noted, that Bach did not use this time to relax but rather to aid in the composition of larger works, such as the St. Matthew Passion). All in all, some sixty cantata performances would be required of Bach per year. This monumental task of creating yearly cantata cycles, or Jarhgänges, would take the composer a great deal of time and effort. Bach ended up composing music for five complete Jahrgänges, totaling roughly three-hundred cantatas (of which just over two-hundred survive today). To aid in the completion of the first yearly cycle (1723-1724), Bach assimilated many of the earlier compositions from his time in Weimar and Cöthen. Cantata number 105, however, was not one of these earlier adapted cantatas, and must have been composed shortly after Bach’s Leipzig appointment, and was perhaps being formulated while Bach was moving from Cöthen in late May 1723. Whenever its composition, we do know that the work was a part of the first Jarhgang, first being performed on 25 July, 1723-- the ninth Sunday after Trinity. Structure Cantata number 105 is a six-movement work, consisting of an opening chorus, followed by a recitative, an aria, another recitative, another aria, and finally, a chorale. This form was much-adhered to by Bach in this time, and its order can be found in many of the first Jarhgang’s cantatas-- the works for the eighth through fourteenth, twenty-first, and twenty-second Sundays after Trinity all follow this structure. Reasoning for the order described is to be found in the Lutheran sermon, which Bach constructed musically as an opening and closing chorus with pairs of recitatives and arias in-between, which would serve as commentary on the scripture usually found on either side of it. A basic and large-scale key structure appears as this: Mvt. I Mvt. 2 Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht Mein Gott, verwirf mich nicht Chorus Recitative- alto g minor c minor moves to B-flat major Mvt.3 Mvt. 4 Wie zittern und wanken Wohl aber dem, der seinen Bürgen weiss Aria- soprano Recitative-bass E-flat major B-flat major moving to E-flat major Mvt.5 Mvt. 6 Kann ich nur Jesum mir zum Freunde machen Nun ich weiss, du wirst mir stillen Aria- Tenor Chorale B-flat major B-flat major moving to G The order of tonal centers appearing as : Movement: I II III IV V VI Tonal center: g c--B-flat E-flat B-flat-E-flat B-flat B-flat-G | Center of key movement One interesting aspect of this order of keys is that if we take take the fifth tonal center found in the fourth movement, B-flat, and travel right or left, the succession is nearly the same, differing only at c and B-flat, respectively. There is a chiastic nature to this cantata which is difficult to ignore, and will be subsequently discussed. Furthermore, another common feature of Bach’s cantatas is to be found in the text of the present work: the procession from death and judgment leading to eternal life and salvation. Movement 1: Chorus Herr, gehe nicht ins Gerich mit deinem Knecht. Lord, do not pass judgment on your servant Denn vor dir wird kein Lebendiger gerecht For before you no living creature is justified This text, taken from Psalm 143, verse 2, is what we are first presented with at the beginning of the cantata. The structure of this movement is more complex than that of the others, as it exists in two, clearly defined sections. The movement is set up, like as in so many other opening movements of Bach’s, as a prelude and fugue. The movement as a whole consists of 128 measures: the first 48 are the prelude, while the latter 80 make up the fugue. The prelude can be broken down into several smaller sections Bars 1-48: Prelude 1-9: Opening instrumental (A) 9-15: Chorus enters (B) 15-23: Instrumental interlude (A1) 23-29: Chorus (B1) 29-42: Chorus (C) 42-48: Pedal on V The first eight bars introduce the cantata as a thoroughly chromatic one, going through twelve tonal centers in these bars alone! (see example 1 below) The first entrance of the chorus, as in all entrances of the chorus in the prelude section of this movement, is staggered. The tenor comes in first (on the fifth scale degree over the V chord), and is followed on consecutive beats by alto (on the second scale degree, also on the V), then the bass (on the first scale degree on the i chord), and finally by the soprano (on the fourth scale degree and over the iv 6/4 chord.). The voices remain for the most part at the rhythmic separation of a quarter note, singing extremely similar lines and occasionally pairing up in rhythmic unison. The second instrumental section, from bars 15-23, is very similar to that of the first, containing the same number of modulations but all up a perfect fifth. When the chorus enters at bar 23, we are given a different order of entry: Beat 1 is the alto (again, on the fifth scale degree and over the V chord-- though now in d minor), beat 2 is the soprano (again, on the second scale degree over the V chord), beat 3 is again the bass (with the first scale degree over the i chord), and beat 4 belongs to the tenor (again with the fourth scale degree over the iv 6/4 chord). This section, from bars 23-29, is very similar to that of the first choral section, with a main exception being made in the case of the orchestra, which is now playing an independent role (not just continuo), and is thrust more into the foreground than it was before (see example 2 below). In bar 31 the last vocal entry of the prelude section comes in, this time different from the two prior-- whereas the first two entries start on the first beat of the bar (on V), this entry begins on beat 3 of bar 31 (on I in B-flat major)(see example 3 below). The order of entry is now soprano on beat 3, alto on beat 4, bass on beat 1 of the following bar, and tenor on beat 2. This section is also twice the length of the previous two choral sections, at 12 bars. There appears to be some significance to this number: the reading for the date on which cantata no. 105 was performed, the 9th Sunday after Trinity, was Luke 16:1-9, which features Jesus telling a story of a lost steward to his twelve disciples. Twelve modulations in two separate orchestral passages and a choral passage lasting twelve bars, in addition to the text, clearly point to this reading from Luke. Furthermore, Bach’s heavy use of chromaticism and the famed “sigh-motif” appoggiatura (see example 4 below) symbolize the guilt and remorse felt both by the steward in Luke 16 and the speaker in Psalms 143 (the stanza after the one chosen for this opening chorus is similarly lacking in optimism: The enemy pursues me he crushes me into the ground he makes me dwell in darkness like those long dead Bars 42-48 of the prelude serve, in their function as a pedal V, as a setup for the fugue which follows, starting halfway through bar 47. Here Bach readies his listeners’ ears for the upcoming allegro by shortening the rhythmic values in the upper voice in these pedal bars-- here, for the only time in the prelude, we have an ascending trio of 16th-two 32nds. This will be reflected in the opening bars of the fugue with an ascending trio of quarter- two 8ths in cut time. The fugue starts on the third beat of bar 47 and, as in the case of the prelude, the tenor has the first entrance. The second line of the text (“For before you no living creature is justified”) is used as the basis for the following 80 bars. There are, again, twelve entrances of the fugue theme before the section comes to a close, shown in the following chart: statement: i ii iii iv v vi vii viii ix x xi xii measure: 47 52 57 62 67 72 77 82 93 98 115 120 voice: tenor bass sop. alto bass tenor alto sop sop. bass bass bass tonic: g d g d g d g d g d g c The sixth, seventh, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth entrances are doubled in the continuo line. As most of the entrances are punctuated at a distance of five bars, it is worth noting that in two instances this gap is greater: between the seventh and eighth entrances, where the distance is eleven bars; and between the tenth and eleventh entrances, where the distance is seventeen bars. Here, Bach writes in episodes; like many of his fugues, the episodes increase in length as the movement progresses. It is in the second of these episodes, in between the tenth and eleventh entrances, where Bach has the only change of texture in the entire first movement. Up until now, there has been consistently thick writing in the vocal part. At bar 108, however, the bass drops out and a thin, effervescent orchestra part accompanies in its upper registers (see example 5 below). This chilling effect is dismissed eight bars later, when the bass joins in for its last two entrances. The twelfth and last entrance is at first deceptive (this deception mirrors that of the original twelfth apostle), entering first in g but later, in a truer sense, in c. The movement comes to a close shortly thereafter, solidly in G major. Movement II- Recitative Mein Gott, verwirf mich nicht, My God, do not toss me away, Indem ich mich in Demut vor dir beuge since I bow down before You in humility Von deinem Angesicht. before Your countenance. Ich weiss, wie gross dein Zorn und mein I know how great your wrath and my Verbrechen ist, Crime is, Dass du zugleich ein schneller Zeuge that You are at once a swift witness Und ein gerechter Richter bist. and a righteous judge. Ich lege dir ein frei Bekenntnis dar I lay before you a free confession Und stürvze mich nicht in Gefahr, and do not plunge myself into danger, Die Fehler meiner Seelen by denying or concealing Zu leugnen, zu verhelen! the faults of my soul! The second movement of BWV 105 is an alto recitative, the text of which deals with first facing judgment and coming to accept responsibility for one’s sins. As there exists such a spiritual journey taken in the text, the reasoning for Bach’s journey through keys becomes apparent. The first four bars solidify our tonal center as C (C minor, in this case). The next stanza is spent in f minor before, halfway through the movement, Bach brings the tonality home to g minor. The last stanza returns quickly to F before, through the means of a “plunging” bass reflected in the text (see example 6 below), modulating to B-flat in a rather dramatic fashion. As the speaker talks of denying or concealing the faults of his soul, so is the modality concealed of our B-flat tonal center by the introduction of the lowered sixth scale degree in bar twelve, stacked upon an already-unstable V7 chord in third inversion. After this V7 chord, however, Bach does not yet provide us with the anticipated I chord in first inversion, but he rather opts for an increase in tension by going backwards in the circle of fifths-- to an altered II chord without its root (see example 7 below)-- before bringing the movement to a close with a V-I cadence. Movement 3 Wie zittern und wanken How the thoughts of the sinner Der Sünder und Gedanken, tremble and waver, Indem sie sich untereinander verklagen while they make accusations among themselves Und wie derum sich zu enschuldigen wagen and again and again try to excuse themselves So wird ein geänstigt Gewissen Thus an anxious conscience Durch eigene Folter zerrissen is torn apart by its own torment The third movement of the cantata is what originally attracted me to the work as a whole; I was dedicated to this work before I had heard any other of its movements. This soprano aria is notable for a few features, the first and most prominent of which is the fact that there is no bass. In its place there instead exists a shimmering, pulsating tremolo in the strings, with the violas sounding the lowest part. The reasoning for this particular textural setting becomes apparent as the text is slowly revealed to the listener. The lack of a fundamental lower part reflects the lack of moral grounding expressed in the anonymous text, and the shimmering in the accompaniment (which in different parts moves along at different subdivisions of the beat) reflects the “trembling” and “wavering” of the sinner’s thoughts (see example 8 below). As Christoph Wolff writes, " The development of interpretive imagery in Bach’s musical language also took a new turn in the first months at Leipzig. For example, and aria like “Wie zittern und wanken/ der Sünder Gedanken, /indem sie sich untereinander verklagen” (How tremble and waver/ the sinners’ thoughts/ in that they accuse one another), of cantata BWV 105, translates the poetic text precisely into a fitting musical idea...First of all, the rhyme structure of the initial lines of the poem (wanken/ Gedanken) determines Bach symmetric phrasing of the corresponding vocal declamation. Then, the texture of the setting is fashioned to represent the image of “trembling and wavering” simultaneously by a two-layered score: the motive of wavering thoughts in the floundering and halting melodic gestures that alternate between soprano and oboe in an overlapping manner, and the trembling thoughts in a string accompaniment based on a tremolo figure that proceeds, for purpose of intensification, at two different speeds...” Other rhetorical gestures occur over certain words: for example, over “accusations” and “excuse themselves," Bach writes florid and melismatic passages, symbolizing the wordy pleading of sinners. Furthermore, the oboe appears as an afterthought to the soprano line, serving as virtual thought bubbles rising out from the speaker’s head. Structurally, this movement is in three sections: the first is from the beginning to measure 45; the second lasting from 45 to 77; and the third lasting from 77 to bar 109 (at the end of the movement there is a Dal Segno, at which point the opening instrumental prelude from the beginning of the movement is repeated; bar 109 is actually bar 17). Key movement appears roughly as follows: A (beginning-45) B (45-77) C(77-109) E-flat to B-flat B-flat to c c to E-flat This movement of tonal centers appears to be, at first glance, quite similar to the first half of the entire cantata: Cantata: g c-B-flat E-flat B-flat-E-flat Mvt.. 3: E-flat-B-flat B-flat - c c - E-flat And, upon closer inspection, the keys of the third movement actually are recalling the keys of the movements which have preceded it in reverse order: Mvt.. 3: E-flat Mvt.. 2: B-flat to c Mvt.. 1: g Movement 4 Wohl aber dem, der seinen Bürgen weiss Yet it is well for him who knows his Indemnitor Der alle Schuld ersetzet who make reparation for all guilt, So wird die Handschrift ausgetan, for the signature disappears Wenn Jesus sie mit Blute netzet. when Jesus moistens it with His blood Er heftet sie ans Kreuze selber an, He himself lifts us up on the Cross, Er wird von deinen Gütern, Leib und Leben, He will hand over the account of your goods, body, and life Wenn eine Sterbestunde schlägt, When your hour of death strikes, Dem Vater selbst die Rechnung übergeben. to the Father himself. So mag man deinen Leib, den man Therefore your body, which is carried to the ,zum Grabe trägt grave, Mit Sand und Staub beschütten may well be covered over with sand and dust Dein Heiland öffnet dir die ewgen Hütten while your Savior opens the eternal courts for you The fourth movement of cantata 105 marks a special point in the work as a whole: this is where the middle tonal center occurs, and it is also the point which helps to define the key movement of this cantata as nearly-palindromic. More importantly, however, this is the point which makes this cantata chiastic. Chiastic structure is a common form found in, among other idioms, literature and music. Deriving its name from the name for X is Greek, “Chi," chiastic structure in liturgical music often resembles the shape of a crucifix in large-scale structure. Walking along one end of Jesus’ crucifix, we would start furthest away from Christ. In the middle, we would encounter both the end of physical life and Christ, and as we depart, we finally reach salvation and eternal life. Further evidence for chiasticism in this movement is found in its role as a bass recitative-- Bach frequently favored the bass as playing the role of Christ (as seen in the Passions). The text of this recitative fulfills all of the expectations we might have if we a suspected chiastic form in this cantata. Each movement preceding this one expresses the fear of a vengeful God, of human fault and lack of righteousness. This movement, however, is the first which speaks of salvation through Christ. It is in this movement in which we find mention of Christ’s blood acting as a voucher for salvation, just as we would encounter Christ’s body at the intersection of his crucifix. Further imagery is found in the “tick-tock” of the pizzicato continuo part, a rare effect which Bach surely reserved for the ominous “Sterbestunde” referred to in the second stanza (see example 9 below) The texture of this movement is constant throughout: the strings are once again resigned to an ostinato (though this time, melodic) accompaniment. Their triads move in rhythmic and directional unison for the duration of this recitative, which because of its constant motion and melodic writing for all parts feels somewhat like an aria. There is one break in the texture of this movement, which occurs over the text: Therefore your body, which is carried to the grave, and specifically, over “body," which may have rhetorical origins: here, the middle two accompaniment voices stop their ostinato pattern and adopt instead a sustained diad-- it is this diad which is “carrying” the upper accompaniment voice. (see example 10 below). After this break in texture, the accompaniment join together for four short beats before departing their arpeggio pattern and bringing the movement to a close. Movement 5 Kann ich nur Jesum mir zum Freunde machen, If I can only make Jesus my friend So gilt der Mammon nichts bei mir then Mammon is worth nothing to me. Ich finde kein Vergnügen hier I find no pleasure here Bei dieser eitlen Welt und irdschen Sachen in the midst of this vain world and earthly objects. The fifth movement of cantata 105 is the only one which might be described as being “upbeat," and this characteristic reflects the optimism found in the text. Here, the speaker is striving to make Christ his “friend," and is abandoning material wealth in the process. The anonymous text mentions “Mammon," which provides an interesting image of the battle between earthly possessions and salvation. Mammon, demon-god, was often pictured wearing rich, royal gowns and sometimes holding bags of money. Furthermore, he was frequently seen with sinners worshipping at his feet (see below), an obvious reference to man’s all-too-reliable characteristic of correlating material wealth with social success. There is a small amount text for the length of the music and because of this, Bach is required to repeat lines of poetry time and time again (see example below). This brings to mind a criticism leveled by Johann Mattheson while in Leipzig, in 1725: "In order that good old [Friedrich Wilhelm] Zachau may have company, and not be quite so alone, let us set beside hum an otherwise excellent practicing musician of today, who for a long time does nothing but repeat: “I, I, I, I had much grief, I had much grief, in my heart, in my heart. I had much grief, etc., in my heart, etc., etc., I had much grief, etc., in my heart, etc., I had much grief, etc., in my heart, etc., etc., etc., etc., etc. I had much grief, etc., in my heart, etc., etc.” Then again: “Sighs, tears, sorry anguish (rest), sighs tears, anxious, longing, fear and death (rest) gnaw at my oppressed heart, etc.” Also: “Come, my Jesus, and refresh (rest) and rejoice with Thy glance (rest), come, my Jesus (rest), come, my Jesus, and refresh and rejoice....with Thy glance this soul, etc.” This aria, the second and last of the cantata, is for a tenor. So far, the solo vocal movements have appeared in this order: Mvt. 2: Alto (recitative) Mvt. 3: Soprano (aria) Mvt. 4: Bass (recitative) Mvt. 5: Teor (aria) This order has appeared twice before, in the opening prelude-fugue movement: First, it appears in the second entry of voices in the twenty-third bar of the prelude section (see example 3). It appears again as the entry of fugues, though in reverse order. This area is in three distinct sections. The first lasts from the beginning to bar twenty-two, and serves the purpose of modulating from B-flat (I) to F (V). The second section is lasts from twenty-two to forty, and returns to B-flat from F. The last distinct section is from bar forty to bar 54, and modulates from c to d minor. There is a Da capo which repeats the first two sections before coming to a close solidly in B-flat. The Da capo ostracizes the third section of this aria, and it is further highlighted by the fact that is the true minor-key “representative” of the movement. Reasoning for this highlighting can once again be found in the text which accompanies this movement. The lack of happiness in this section’s modality can be attributed to the lack of happiness in the text: Ich finde kein Vergnügen hier I find no pleasure here bei dieser eitlen Welt in irde’schen Sachen. in this world and in Earthly objects. However, as we now find ourselves on the “salvation” side of this chiastic cantata, it makes sense that Bach would use a Da capo to end the movement on an hopeful note, over the more optimistic text: Kann ich nur Jesum mir zum Freunde machen, If I can only make Jesus my friend So gilt der Mammon nichts bei mir then Mammon is worth nothing to me. The texture is unsurprising; the orchestra is full and mostly homophonic (with additional cornet), excepting of course when the tenor enters. There are short orchestral interludes separating each section-- four bars in between the first and second section, and ten bars between the second and third sections-- which give this particular aria, with its distinct declamatory style, the feeling of antiphony. One particularly notable feature of this movement is its ability to reveal the quality of Bach’s orchestra: before, he had written the virtuoso parts for his vocalists (in particular his soprano). Now, we have evidence for the very capable musicians of his Leipzig orchestra in the violin part of this aria. The part is almost needlessly virtuosic in its florid and hurried movement; one gets the impression that Bach is using movements of this cantata as showpieces for his new orchestra (see example 11 below) This particular violin part in fact brings to mind J.S. Bach’s debut as concertmaster in Weimar in 1714: “For cantata performances under Bach’s direction, it is safe to say that the concertmaster led the capelle from the first violin. Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach writes that 'in his youth, and until the approach of old age, he played the violin cleanly and penetratingly, and thus kept the orchestra in better order than he could have done with the harpsichord.' So it is particularly appropriate that in performing his first cantata under the new arrangements, Bach presented himself simultaneously as composer, concertmaster, and violin soloist. The absolute leadership role of the concertato violin in the opening movement of BWV 182 is clear from the first measure, as it is in the first aria (no. 4).” Movement 6 Nun, ich weiss, du wirst mir stillen Now, I know, You shall quiet in me Mein Gewissen, das mich plagt. my conscience which plagues me Es wird deine Treu erfüllen, Your faithful love will fulfill Was du selber hast gesagt: what You Yourself have said: Dass auf dieser weiten Erden that upon this wide earth Keiner soll verloren werden, no one shall be lost sondern ewig leben soll, rather shall live forever, Wenn en nur is Glaubens voll. If only he is filled with faith. The last movement of cantata no. 105 is, as in so many others of Bach’s other cantatas, a chorale. Here, Bach uses (for the first time since the first movement) all four voices in differing levels of homophony and polyphony. The chorale melody in this case is “Jesu, der du meine Seele," written by Johann Rist. This particular melody is the only of Rist’s that Bach used in his chorale writing, though he used several of Rist’s texts for other vocal works. The text of this chorale serves as an endpoint to the strife and turmoil with which we were assaulted over the course of the preceding five movements. Assured by his faith, the speaker is confident that he will “live forever” and that “no one shall be lost." While this movement does not stray very far from its roots in G (see diagram 1 on page 25), it should be noted that Bach does occasionally stray from major and minor tonality and into church modes. The transition to a straight major/minor harmonic language was still relatively new to composers of Bach’s era-- composers who were thoroughly trained in the church modes. J.S. Bach had a thorough knowledge of the high Renaissance, and he drew off of this for a great deal of his chorale writing. Reasoning behind the use of old church modes chorales such as the one which closes cantata BWV 105 were, to some extent, documented by Bach himself-- in a response to criticism regarding his compositional process at the beginning of the 1740s by Scheibe: “At the beginning of this decade we find between Scheibe and Birnbaum the aesthetic controversy concerning Bach’s compositional style. Bach did not get directly involved in the discussion, but he clearly used Magister Birnbaum of the University of Leipzig as his very own spokesman. One can recognize this on the basis of the argumentation regarding Scheube blaming Bach for the absence of a main voice (“Haupstimme”) in his music. Bach then explained his understand of harmony and polyphony in terms of historical examples, specifically citing works of Palestrina and others. He clearly attempted to give his compositional convictions historical dimensions and authority. At the same time (the later 1730s), Bach was surrounded by a number of very gifted theory students: Mizler, Kirnberger, Agricola, for example. Thus, it is not at all a surprise that, for the first time, in Clavier -Übung 3 (1739), Bach included a strong theoretical-historical component introducing a new dimension in his personal style. This is evident in his systematic approach to dealing with the old church modes (aiming at an enrichment of the standard major-minor tonality)...” Bach’s later interest in Mass-writing and in the vocal music of Palestrina were also clearly evident in this earlier work. This affinity for the stile antico of past masters would gradually become more and more apparent in his musical output: “...Thus Clavier-Übung 3 demonstrates Bach’s continuing preference for sixteenth-century chorale material, which he had also used in the 1724-1725 cycle of cantatas. Moreover, Bach’s choice of hymns seems to have implied some crucial aspects of compositional technique as well, especially with regard to the emphasis on church modes. Bach was now able to explore modal harmony in a rather systematic way, thereby extending the limited tonal vocabulary of the major and minor modes.” Bach uses texture and rhythm to show us the end of this cantata is near: a 16th-note ostinato part for the strings, similar to that found in the soprano aria, BWV 105/3, starts out the movement in an accompanying role. As the work progresses, however, this ostinato is slowed to a triplet rate. Later, this is further stretched to straight 8th-notes, then quarter-8th in triplets, and then finally to just quarters. Each couplet of the hymn text receives two treatments of these continually-increasing rhythmic values. Though there has been no change of tempo, the listener is left with the impression that the movement has slowed to a crawl; there is no other option but for the music to end (see example 12 below) Another strange aspect of the texture of this chorale is that the vocal part is not continuous: usually, a chorale of Bach’s features vocal music uninhibited by its accompaniment and punctuated only by fermata. However, in this particular movement, after a line of the hymn is sung, the voices will stop and the orchestral accompaniment will continue on (see example 13 below). Reasons for this are at first difficult to attain: when the orchestra continues to wander after a fermata, it wanders with only the three top strings, without the bass. These three instruments--violin 1, II, and viola-- are the trio which will provide the ending chord. They also happen to be the trio which accompanies the soprano in the third movement, again without bass. The continuo part starts up again with the text. This must be an allusion to the text, which is describing the salvation that is to be found in faith. When that message is not there, neither is the fundamental salvation that it brings along with it. The study of Bach brings about a greater appreciation for the composer. This is true for the best composers of the so-called “Common Practice," from Bach’s time to Mahler’s. Bach is somewhat of an anomaly in that you need not know anything about how music works in order to recognize his technical mastery, or to float (or sink) in the complexity of his music.

It is easy to become overwhelmed by a great composer’s knowledge of music. But rarely is there an example of a composer who knew so much outside of the craft in which he chose to dedicate himself. How readily this becomes apparent can be startling, especially when tackling such a large-scale work as one of Bach’s cantatas. In this analysis, I cannot help but feel like I’ve merely scratched the surface of Bach’s ocean of knowledge, the DNA of which is carefully tucked away and hidden amongst rhetorical gestures, or in multi-movement structure. The exercise has been both enlightening and humbling!

1 Comment

|

Categories

All

Archives

August 2023

AuthorYouTube |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed