|

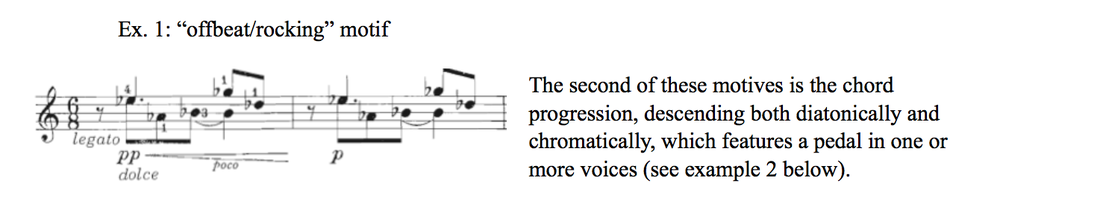

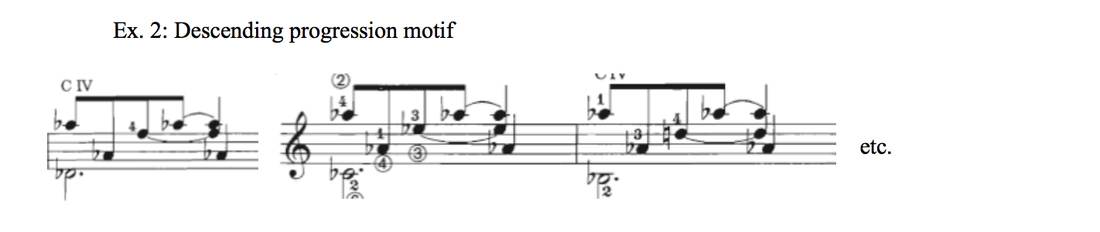

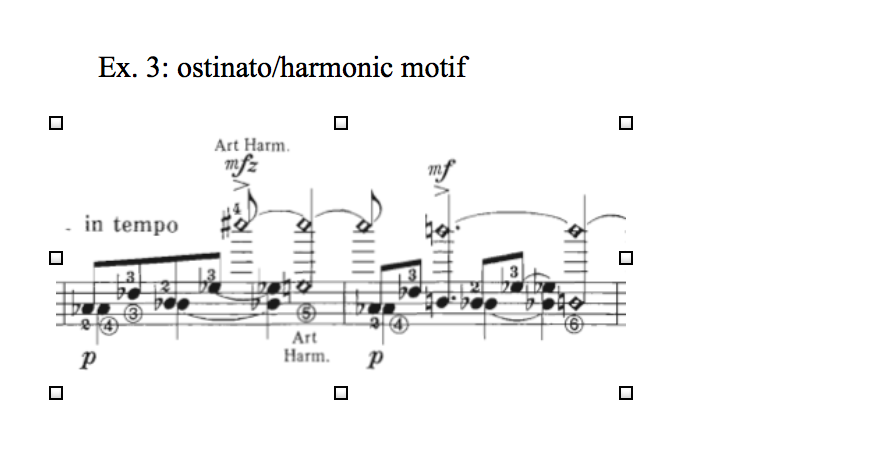

The first motif of this movement makes itself known from the first two pitches, e and c. There are a few characteristics about these pitches which embed themselves into the fabric of the work. First, the pitches themselves are structurally important, as they bookend the piece: the first two notes are e followed by c, and the last two chords are a [01368] chord whose root is C followed by a [01358] chord whose root is E. Secondly, the movement by a third, in both its major and minor versions, appears again and again in different voices. Another alternation-motif whose recognition is crucial to the performance of the work is that between the “non-tonal” [01368] and “tonal” [01358]. Alerting oneself to these important motives lends itself not only to an understanding of phrasing which is grounded in something more than “sounding right”, but also to a more highly integrated performance of the movement as a whole. The large-scale structure of this movement is more readily accessibly by Takemitusu’s cutting-and-pasting of nearly fifteen measures (mm. 29-43 are copied from mm. 4-18). In a composition lasting sixty bars, this gesture would significantly add to the feel of symmetry if it weren’t for the composer’s addition of the third section which closes the work. In effect, the structure flows as follows: A: mm. 1-19 B: 20-29 A: 29-43 C: 44-60 The first section is partly defined by its overwhelming presence of [01368] harmonies. This chord first appears in the second bar, and is heard again in the seventh and nineteenth. Because Takemitsu leaves out measure 19 in the restatement of the first section, we are left with only one occurrence of the harmony, in 32. In this section we also find the “movement by a third” motif en masse. The first two notes of the composition highlight the descending major third from e to c, and these pitches occur once again in the melody of bar 4. The phrase starting in 10 has a g descending to a d# in the melody, and in 13 d# descends by another third to b. A melodic ascending minor third occurs twice in measures 17 and 18. Ascending compound minor thirds can be found in the [01368] as the last two notes of measures 2, 7, and 19. Special attention should be drawn to 15, in which the compound third interval is that of an ascending major third. This anomaly is thrust into the spotlight even further when we realize that is occurring in the midst of the only [01358] present in this section. Whereas the A section of the work was dominated by the affluence of [01368], the B section responds with a show of the much more consonant [01358]. Bars 20 and 21, as well as the downbeat of 22 all contain the harmony. Measure 27 also displays a [01358] but also introduces a “sextuplet” motif in the melody. This motif is reserved only for [01358] harmonies, and it serves as a mold for much of section C’s rhythmic material. The downbeat of 29, with its [0247] harmony, is harmonically distant from the characteristic chordal material of the work and serves here as a pivot point back into the repeated A section. Meanwhile, measures 20-29 have their fair share of “movements by a third.” The bass in 23 ascends a minor third, while middle voices of both 22 and 23 feature an ascending minor third and descending major third respectively. The last two notes of 26 and 28 close the B section cloaked in the guise of ascending minor thirds, to which further attention is drawn by Takemitsu’s use of natural harmonics. The last section of the work (44-60) provides symmetry for the repeated A section in that it is, like the B section, overwhelmed with consonant [01358] harmonies which very much lend themselves a “tonal” feel for the closing bars of the movement. In jazz terminology this chord would be called a “minor 9”, and its heavy use here may be hinting at the prevalence of “jazz” chords to come in the forth movement. 44, 45, and 46 immediately feature three consecutive utterances of the harmony, as well as the return of E and c in the bass. The movement from E in the lowest voice of 44 up a sixth to the bass’s c in 45 makes one wonder if the composer had wished instead to descend to C lower than the last string of the guitar in order to maintain motivic unity. Takemitsu was no stranger to scordatura tunings for the instrument, but never does he drop the sixth string lower than a whole-tone below E. Much as [01358] made only one exhibit in the A section, [01368] makes its only appearance of this section in in 57-58, along with its final two notes forming an ascending compound minor third. The last harmonic f of the chord in 58 here serves as a leading tone to the harmonic f# which rides high above the closing [01358] chords of 59 and 60. Movement IV: Slightly fast Excepting the composer’s pop music arrangements, the last movement of All in Twilight surely ranks among Takemitsu’s most tonal works. There are very few instances in which the listener is made left unsure as to what the tonal center and at those moments, any uncertainty can labeled as jazz-like extensions of tonal elements. The harmonic world here is the one most audiences are accustomed to, in which cadences go from V to 1, not [01368] to [01358] as in the first movement. In this movement we again find the composer cutting and pasting substantial portions of the work to create symmetry which otherwise might not exist. However, he allows himself more freedom to develop motives and ideas presented early on in the movement than he did in the first. The work is further imbued with pop-liness through its nearly-constant use of 6/8, though this meter is occasionally utilized in non-traditional ways. Each section of this movement is characterized by its use of three motive which appear in the first page of the score. The first of these is the “offbeat/rocking” ostinato motif which opens the work (see example 1 below). The last of these motives is related to the first in that it is an ostinato, but dissimilar in that high-register harmonics punctuate its texture (see example 3 below) All of the movement is related in one way or another to one of these three motives, and Takemitsu’s weaving and blending of these themes creates a work which is at once unified and easily accessible.

The opening measures places the tonal center at A-flat, and the harmony is tinged with a distinct mixolydian flavor. Melodic entry occurs at bar 4 via the artificial harmonic c, which then travels to b-flat, then to e-flat. This is repeated an octave lower in 7 before transitionary material derived from the rocking motif, over an altered V chord in 11 (Ab7 with b9/#9), brings the listener to the next section. Bar 12 is illustrative of the descending chord progression motif and although the motif feels more “tonal” than any of the others, analyzing it as such quickly becomes pedantic. Much more satisfying is viewing the progression as a series of “jazz” chords whose voice leading has been paid extra-special attention. With so much A-flat mixolydian baggage, a D-flat chord has no choice but to sound as tonic. This modulatory distinction, however, is ultimately meaningless: if this work were to end in clichéd bliss on a D-flat, we would all be greatly disappointed. The progression, starting in measure 12, is as follows: D-flat : first inversion A-flat minor: B-flat 7: first inversion f# minor: A-flat 7: G major 7. The a tempo in bar 18 delivers for the first time the ostinato/harmonic motif, which leads quickly back to the first rocking motif in 22. Here the melodic motion in harmonics reflects that of measures 3-5 and 7-10: descending 2nd followed by descending fourth. 26-29 is a repeated two-bar iteration of [013469] chords, ascending by minor third, riding atop the rocking motif. Measure 29 cannot be helped from sounding like another altered V chord (V7 with added 6 and b9) preparing us for the new tonal center of A at 30. The descending chord progression motif is here featured for three measures before a combination of the offbeat/rocking and harmonic motif in 33 presents us with another form of the descending chord progression, now in d, at 34. Measures 37-40, derived from the offbeat/rocking motif, are playing what might be an unprecedented role in Takemitsu’s music: a ii-V-I progression in Db! While the enharmonic spelling at first prevents us from seeing it as such, measure 37 and 39 contains an Eb half-diminished 7 chord (ii), while 38 and 40 both spell out an Ab13 (V). This naturally leads to a sense of tonic at Db in 41. Here we have the descending progression motif with the same bass movement as its first presentation in bar 12, though now with the chords altered with “jazz” notes in the form of the offbeat/rocking motif. The progression is now as follows: D-flat: first inversion A-flat minor: B-flat 7 with b9/#9: first inversion f# minor with b5/b9: A-flat 7: g minor 9 The last four eighth notes of measure 44 could be analyzed as an A7 b9 with no root. Taking this view of the chord allows for another V-I progression in D at bar 45. Here is another 3-bar iteration of the descending progression motif, immediately after which follows a repeated, “rocking”, 3-bar [01469] which is now descending by minor thirds. From 52-73 Takemitsu repeats measures 3-25, though now with the altered descending progression of 41-44 in place of the prototypic 14-17 version. Bars 73-74 serve up one final V-I, now with the original tonic of A-flat. While the penultimate bar might at first resemble the dreaded clichéd ending, Takemitsu saves us in the last by filling out the A-flat 9 harmony. As with the first movement, an harmonic f# in the highest voice brings the work to a close. Tracking the movement of tonal centers throughout the movement, we are able to see harmonically engrained symmetry. m.1: Ab 11: Db 18: Ab 29: A 33 d 40: Db 44: D 51: Ab 60: Db 66: Ab While the performer, and in turn the audience, may have something to gain by analyzing the music of Takemitsu, part of its appeal lies in the fact that the composer was accepting of all systems, and--in effect-- dismissive of a unifying one. All in Twilight is truly a composition that is the product of a multifarious musical and psychological upbringing: had Takemitsu not been born when he was and had the second World War not ended as it did, it could never have possibly been written. Nowhere is this better reflected than in these two movements, which at once are able to show the large diversity of 20th century music as well as Takemitsu’s mastery of different styles.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

August 2023

AuthorYouTube |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed