|

Charles Ives’ Central Park in the Dark is a work from the fruitful period that followed his self-imposed exile from professional music-making. During the years 1898- 1906, Ives more and more removed himself from the German-Romantic harmonies which had dominated his earlier works, instead concentrating on the development of his own personal idiom derived from experimental technical procedures and an emphasis on quotation. The work, whose first title was “A contemplation of nothing serious,” serves as a companion piece to “‘A Contemplation of a Serious Matter’,” or The Unanswered Question.” In the work, we find Ives as a young man in a light-hearted contemplative mood, observing the goings-on of the Park while sitting on a bench by one of its ponds. This sort of immersed, nature-inspired reflection was just one of the ways in which Ives’ transcendentalism-- the set of ideas, attitudes, and questions espoused by thinkers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau-- reared its head. By first examining significant elements within the score, and then by examining some those aspects of Transcendentalism which most immediately relate to music generally, this paper intends to broadly convey Ives’ musical translation of philosophical ideas. Foremost among these ideas are those concerning the importance of a communal, emotional language which can be accessed through quotation of popular materials; that the contemplation of Nature is essential to the well-rounded and dynamic life; and that harmony exists between elements which appear to be opposed to or at odds with one another. Harmonic Elements and Form

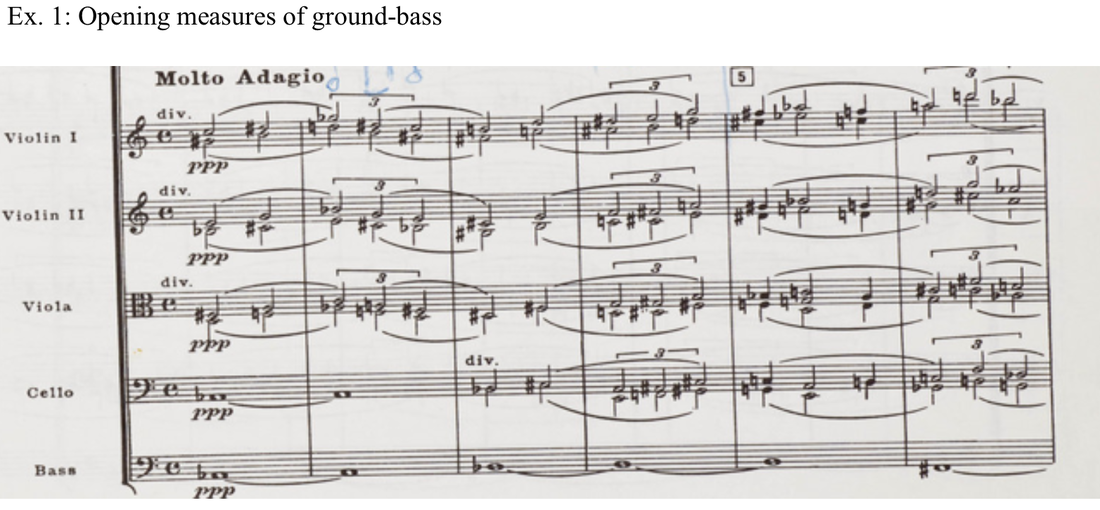

Form in Central Park in the Dark, like many of Ives’ other large-scale works, is unique to the work (Ives believed this allowed the ears of a listener to be freed up from the constant expectation of the next predicted event-- the problem of a listener “thinking about than thinking in music.”). The music is, in a sense, a ground-bass played by the strings (see example 1) over which episodic elaborations are laid in accumulative layers (Ives defines the work as a “contemplation” with “interruptions”). As in Decoration Day, the running time of which should last exactly ten minutes, Ives’ fascination with the number is seen here in that a “ten measure phrase”--the ground-bass-- is repeated ten times. Likewise, there is a parallel to be drawn to his earlier setting of Psalm 24, in which the intervals with which chords are comprised expand in each subsequent phrase. These chords, as in the setting of the Psalm, move in rhythmic unison and oftentimes in parallel motion. For example, in Central Park in the Dark, the first two measures are made up of six-note chords of thirds stacked in such a way that each chord resembles the notes of a whole-tone scale (a pitch set of [0246 10]) over a pedal A-flat (see example 1). When the pedal changes to a B-flat [mm. 3-5], the dominating interval expands to a perfect-fourth. In mm. 6-8 those intervals expand once again to their most dissonant, a tritone, now atop an F-sharp pedal. This dissonance is “resolved” in the last two measures of the phrase (mm. 9-10), in which chords of stacked perfect-fifths are arranged in such a way as to contain the first six notes of a major scale (pitch set of [024579]). With the stage set by the strings, the “interruptions” begin: m.11: clarinet m.21: added flute m.31: added oboe m. 41 : added solo violin and tinkering piano (in premonition of things to come; one gets the sense that this pianist is “warming up”) m.51 all but piano and clarinet go silent m.61 the ragtime band “from the Casino over the pond” and the “pianolas having a ragtime war in the apartment house ‘over the garden wall’” begins with “Hello, Ma Baby” At this point, the two sections of the orchestra—ground-bass strings and ragtime-band—move in different tempi: the strings retain their slow procession of parallel chords while the raucous ragtime band races along with complete disregard to their existence. This interruption is put to a stop when “ a cab horse runs away, lands ‘over the fence and out’, the wayfarers shout”. Following the cacophony of the dance-band across the pond, the ground bass is once again heard prominently (mm. 119), with a duet of strolling violinists heard echoing “over the pond.” Transcendentalism in Central Park in Dark The very existence of Central Park in the Dark can be traced back to Ives’ Transcendentalist ideals: following his graduation in 1898 from Yale, it was with the belief in the holiness of hard work and self-reliance that Ives moved to New York and began working for The Mutual Life Insurance Company in New York City. This decision was further bolstered by his realization that since there was no money to be made in his brand of experimental music, it would be best to concentrate on business without having to sacrifice his voice as a composer for the sake of money. While New York offered Ives an ideal environment in which to focus on his rise up through the insurance industry, it was an artificial setting which undoubtedly left the Nature-loving Ives feeling stifled. Central Park is, for many, the deep inhale which makes the breathlessness of its surrounding madness possible. It is precisely due the starkness of that contrast experienced in the Park (and especially the park “in the dark”) which allows for such dramatic and profound interactions with Nature, rivaling for some those encountered in more famously “natural” environments. Even with the earth and air being “monopolized” as they were with the sounds of “the combustion engine and the radio,” the Park is today still the place where people go to experience that which the City does and can not offer. Natural Contemplation Ives’ writing, of course, smacks of his Transcendentalist upbringing. It is difficult to read him complaining about the influx of noisy technology in the accompanying notes to Central Park in the Dark without remembering Thoreau in the forest, his solace interrupted by “The whistle of the locomotive penetrates my woods summer and winter, sounding like the scream of a hawk sailing over some farmer’s yard, informing me that many restless city merchants are arriving within the circle of the town..”The emphasis on Ives’ fascination with the Park’s natural qualities are seen in the various names given to the work throughout his lifetime: “Central Park in the Dark in ‘The Good Old Summer Time’” was, in more technological times, renamed as “Central Park in the Dark Some Forty Years Ago.” That Ives escaped to the Park’s natural surroundings often enough to compose one of his most profound and perfect recreations of a “transcendentalist symphony” (as he would call Thoreau’s ideal auditory experience of nature) is squarely in-line with what we would expect from a composer so thoroughly steeped in the admiration for and nearly-religious experiencing of Nature prescribed by those Concordian thinkers. For Ives in 1906, the Park was a Walden-proxy, and as this proxy it served beautifully as inspiration for his brand of programmatic/ impressionistic music born from the contemplation of Nature. As the composer himself wrote, “And if there shall be a program for our music let it follow his [Thoreau’s] thought on an autumn day of Indian summer at Walden—a shadow of a thought at first, coloured by the mist and haze over the pond: ‘Low anchored cloud Fountain head and Source of rivers… Dew cloth, dream-drapery-- Drifting meadow of the air ‘” Ives’ interpretation of Thoreau had real implications for his music and for Central Park in the Dark specifically; that the first intrusions upon the affirming serenity of the strings’ ground-bass are made by woodwind instruments is not insignificant. Ives’ use of the flute, clarinet, and oboe-- the sounds of which are more intimately connected with natural sounds than most others-- speak to the influence of such considerations upon Ives’ orchestration. Ives’ oboe here is not the instrument of false majesty which Brahms utilizes in his Violin Concerto; rather, it is the primordial one of the title role of Wagner’s Siegfried: reeds vibrating as air passes innocently among them. Quotation As Emerson noted, “A man will not draw on his invention when his memory serves him with a word as good.” It is difficult to think of an American classical composer who quoted with more enthusiasm and originality than did Charles Ives, whose works are fluent not only in a groundbreaking harmonic language but also in the language of the popular consciousness. By drawing on and toying with the awareness and lifelong attachment with which people had imbued these popular melodies, Ives is allowed more direct access to their emotional state than he would otherwise would have. This tone poem is almost purely descriptive, and when Ives sets popular tunes within the work they seem to work toward a different and more literal end than those set into works such as Decoration Day, which serve a more symbolic purpose, a means of communicating or eliciting a conditioned attitude or response to an occasion at which one would find those tunes being played. Unity through Chaos Thoreau speaks of the unity which is found from disparate sounds placed at appropriate distance: “ All sound heard at the greatest possible distance produces one and the same effect, a vibration of the universal lyre..” In another passage, he identifies what may be the defining characteristic of Central Park in the Dark: “There came to me..a melody which the air had strained, and which conversed with every leaf and needle of the wood, that portion of the sound which the elements had taken up and modulated echoed from vale to vale.” The varying keys, rhythms, and tempi of Ives’ various “interruptions” do not negatively impact the cohesiveness of the work because they mingle “with every leaf and needle” of the ground-bass progression in the strings, creating an accurate impression of the “universal lyre” which Thoreau writes of. The wide range of rhythmic counterpoint also serves to heighten the independent nature of each interruption but does not detract from their sense of belonging-- the polyrhythm and lack of metrical accent is instead reminiscent of the inconsistent and meandering stroll that time can take during such contemplations. The ground-bass, after all, provides the work’s only constancy and its unifying role as timekeeper is seen in the ragtime section, which presents time moving at two speeds: that of the frenzied intoxication of dance and that of a natural reality. In comments such as “My God! What has sound got to do with Music!” in Ives’ Essays Before a Sonata, the composer’s thinking is seen going deeper than just the level of music’s constituent parts; instead, he is more concentrated on the idea that all things are bound together in a unifying marriage of interconnectivity. The intrusion of each new character set atop the ground-bass at first detracts the listener from this union, but upon subsequent listening it becomes apparent how naturally their emergence and accumulation is. As Emerson writes, “..if the mind live only in particulars [i.e., focused on individual intrusions], and see only differences...then the world addresses to this mind a question it cannot answer, and each new fact tears it to pieces, and it is vanquished by the distracting variety.” Each “interruption” introduced is able to exist on its own merit and is not reliant on any rhythmic or harmonic implications of the ground-bass; for example, the plaintive clarinet melody which enters at m. 11 is more or less in C minor: this key has seemingly nothing to do with the undulating waves of chords in the string which support it; rather, it reflects the transcendentalist idea that seemingly disparate things, when viewed as part of a larger landscape, contribute to a fabric which is woven with more interest and beauty than one in which those chaotic aspects are not present. Conclusion Central Park in the Dark is a prototypical example of Charles Ives’ composition and can serve as a Rosetta Stone for the interpretation of his other works in which meaning seems more ambiguous. The composer, steeped in a thorough transcendentalism from his early days, finds ways of imbuing the large share of his mature works with this philosophy; a study of the work at hand is an excellent primer for the examination and appreciation of those transcendental gems. The lesson of Ives is the same as which Thoreau discovered at the end of his time at Walden: “..if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in commons hours. He will put some things behind, will pass an invisible boundary; new, universal, and more liberal laws will begin to establish themselves around and within him; or the old laws be expanded, and interpreted in his favor in a more liberal sense, and he will live with the license of a higher order of beings.” Sources Carter, Elliot. “Documents of a Friendship with Ives.” Tempo. No. 117 (June, 1976), pp. 2-10. Tempo , New Series, No. 117 (Jun., 1976), pp. 2-10. Online article. Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.usc.edu/stable/943036 Dickinson, Peter.”Central Park in the Dark by Ives; Psalm 25 for SATB and Organ by Ives; A Symphony of Three Orchestras by Carter; Separate Songs by Martino; From 'The Child's Book of Bad Beasts' by Martino; Ritorno by Martino; Complete Choral Music by Barber; A Renaissance Garland by Shifrin; Blue Mountain Ballads by Bowles; Dramatic Overture by Schuller.” The Musical Times. Vol. 122, No. 1666 (Dec., 1981): p. 834. Online article. Echols, Paul C. “The Music for Orchestra.” Music Educators Journal. Vol. 61, No. 2, The Charles Ives Centennial (Oct., 1974): pp. 29-41. Online article. Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.usc.edu/stable/3394638 Henderson, Clayton H. “Ives’ Use of Quotation.” Music Educators Journal. Vol. 61, no. 2, The Charles Ives Centennial (Oct., 1974): pp. 22-28. Online article. Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.usc.edu/stable/3394637 Ives, Charles. Essays Before a Sonata. Project Gutenberg Ebook file, 2009. Ives, Charles. Note from Central Park in the Dark, ed. John Kirkpatrick and Jacques-Louis Monod. Hillsdale, NY: Mobart Music Publications. 1973. Print. Perry, Rosalie Sandra. Charles Ives and the American Mind. Kent, OH: Kent State UP, 1974. Print. Rusk, Ralph R. The Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1949. Print. Thoreau, Henry David. Walden; or, Life in the Woods. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004. Print.

3 Comments

Travis

1/8/2019 07:30:17 am

I am currently in an Orchestral Literature class, and we were assigned as our first listening assignment this piece. I enjoyed your notes and plan on referring back to this article as I continue to listen to this piece. Thank you!

Reply

10/12/2019 10:12:52 pm

In graduate school at the University of Redlands in CA, I had the privilege of doing a report on Charged Ives. My syntopical sourses were a few books: 1. A dissertation recently published as a book by Rossiter, the latest compilation of Ives life and music since Henry Cowels biography on Ives. These two books and another by a lady whose name escapes me, emphasized the unconscious flow in Ives music. At the time, we were listening to Putnams Camp, a valuable introduction to some of his techniques: Simultanity; Polytonality, the separation of two totally discnnected works notated to progress together. Fortunately I listened to, General William Booth Enters Into Heaven, extremely original harmonies with percussive relations. Subsequently, I heard that Aron Copeland had looked at the scores of Ives many songs at Tanglewood and was Impressed. This kind of respect coming from Copeland began the rise of Intersst in his work. Arnold Schoenberg made his famous quote:" There is a great

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

August 2023

AuthorYouTube |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed