|

“Don’t look for too many unmentionable motivations in the Album Sonata. I promised it to a young woman who was very kind to me, in return for a beautiful sofa cushion that she gave me as a present.” So wrote Richard Wagner, nearly twenty-five years after he composed the work in question (2). The little mention which the composer made to this sonata is exclusively dedicated to downplaying its significance; Wagner knew he would be remembered as a composer of dramatic works, not of ‘absolute’ instrumental ones. Aside from Wagner’s relationship with the work’s dedicatee, does this sonata, all but ignored in Wagner studies, offer any insight into a composer for whom so much insight has already been offered up? Little mind has been paid to Richard Wagner’s instrumental music, and even less to his keyboard works. The reasons for this are many: the most oft-repeated is that most of the pieces of substantial length were written in the composer’s earliest compositional period, and have been tossed in along with those other pre-Flying Dutchman works deemed by the composer to be unrepresentative or imitative (3). The more striking and worrisome charge leveled against the keyboard works-- and the works of so-called ‘absolute music’ generally-- is that without the dramatic framework upon which to construct his music-dramas, Wagner’s inspiration failed him time after time. A valuable example of the purely dramatic means by which Wagner drew such enthusiasm is seen in the contrast of two simultaneously-composed works, only one of which had dramatic appeal. Centennial March, commissioned by the city of Philadelphia, is famous for its lack of inspiration: “R. still working, complains of being unable to visualize anything to himself in this composition; it had been different with the Kaisermarsch, he says, even with Rule Britannia, where he had thought of a great ship, but here he can think of nothing but the 5000 dollars he has demanded and perhaps will not get.” (4) Contrasting this are early sketches of Parsifal, written in tandem with the March, in which Wagner pens the exquisite music for the Flower Maidens in Act 2 of Parsifal.(5) The original title of the Album-Sonate, “Wisst ihr wie das wird?,” comes from the Norns’ prologue of Act 1 of Götterdämmerung. (6) An answer to the question, of course, is the end of the current social order with the gods as ruling class. The application of this line from the Norn’s scene has prompted speculation as to what Wagner was referring. For William S. Newman, it “could have referred to anything from concern over his slowed down composing to hints of impending crisis in the Wagner-Wesendonck quadrangle.” (7) When it comes to the one piano work of substantive length from Wagner’s budding maturity, the Album-Sonate for Mathilde Wesendonck, opinions are too few and divided to make any firm conclusions about the work’s proper place in the composer’s output. Judgment of the piece ranges from the effusive (“Neglected Masterpiece of Richard Wagner” (8)) to piano-biased condescension (“Of course, the musical superiority of Liszt’s Sonata in B minor over Wagner’s little one-movement Album-Sonata in A-flat is so manifest as to make any comparison absurd except for this question of influences.....the piano writing in this work is not especially resourceful...”)(9) Such opinions do more to stifle than spurn on interest in the work, and, like the sonata’s sparse representation on concert programs are indicative of the stasis in piano pedagogy and a general lack of information on the work (10). As a consequence, the Album-Sonate is seldom-afforded recognition for having occurred at a crucial moment in Wagner’s development. Beyond this slight, analytical studies of the work are lacking; the findings of such studies would undoubtedly reveal the Sonata as worthier of study than is currently accepted. The Sonata in Time The Album-Sonate represents Wagner’s first significant musical uttering following the six-year compositional hiatus which followed Lohengrin and the composer’s subsequent participation in the 1949 Dresden uprisings.(11) This fact, among other intriguing factors, make the work an especially tantalizing subject of study; its relationship to Liszt’s Sonata in B minor, for example, ranks high among these curiosities. (12) This was a hiatus only regarding musical composition, however, and it is from this period that some of Wagner’s most significant writing on aesthetics come. The most important of these, Opera and Drama (1851), dedicates most of its content to the subjects of its title; it offers, however, some small insight as to how the composer’s feelings towards purely instrumental (or ‘absolute’) music had changed. Frequent modulation to distant keys, Wagner posits in Opera and Drama, is the domain of music which possesses the power to emotionally elevate the specific articulated thought of spoken (or sung) drama; without the direction offered by such modulation of thought, music becomes aimless: “...the capacity extends (as a result of harmonic modulation) to such an inconceivable degree of variety that we can set up alliances between the principal key and those even which are most removed from it... Music had suddenly upraised itself from the ground-tone of harmony. It had extended itself to such colossal and varied dimensions that at last the absolute musician could only lose courage upon finding himself wafting restlessly about with no object in view. Nothing could he see before but an infinite waving sea of possibilities, whilst in himself he was conscious of no object capable of putting them to a definite use... Accordingly the musician was necessarily brought other verge of repenting his extraordinary swimming power...Strictly speaking therefore, it amounted to his confessing himself possessed of a capability which he did not know how to use, it amounted in short to his longing for the poet. This longing was clearly enunciated by that most daring of all swimmers, Beethoven.”(13) Wagner’s opinion here had not changed drastically when, in 1856, he jotted down similar thoughts as the topic of an unrealized essay: “On modulation in pure instrumental music and in drama. Fundamental difference. Swift and free transitions are in the latter often just as necessary as they are unjustified in the former, owing to a lack of motive.”(14) While much thought has been spent on the application of such statements in the search for their application in the composer’s music-dramas, their effect on his absolute compositions has (naturally) been documented to a much smaller extent. Wagner’s adherence to these newly-kindled thoughts is demonstrated admirably in the Album-Sonate, as will be shown in the following analysis. Though the work’s original title is derived from a section of the Ring, it will be shown that its musical material--in themes and keys-- points more toward Tristan; one gets the sense that themes from the Album-Sonate would be naturally transfigured into those of Tristan if some of that work’s drama was stirred into the mix. The Album-Sonate as prototype The most appealing and enticing element of the Sonata is that much evidence points to it as being prototypical; had Wagner had lived much longer after the 1882 Bayreuth Parsifal, his music likely would have borne some resemblance to the Album-Sonate. As Ernest Newman noted, “All evidence goes to show that had his health survived the last inroads made on it by the Parsifal production of 1882 he would have found an outlet for his still considerable musical energy in symphonies and quartets.”(15) The influence of Beethoven was, of course, what pushed Wagner into writing opera in the first place; the latter felt to some extent that absolute music had been pushed to its emotional limits by the former, and that access to more powerful feelings would only be permitted by the union of music (which stirred the emotions more than any of the other arts) with spoken word (which articulated specific thoughts and ideas most directly and effectively). Despite Wagner’s incomparable efforts along those lines, his ideas toward instrumental music were evolving and expanding; his symphonic attempts would have appeared drastically different from those which dominated the second half of the nineteenth century. His ideas were judiciously recorded by Cosima: “He says he will call his symphonies “symphonic dialogues,” for he would not compose four movements in the old style, but theme and countertheme one must have, and allow these to speak to each other.(16) Later, in conversation with Liszt, Wagner implores that “If we write symphonies, Franz, then let us stop contrasting one theme with another, a method Beeth[oven] has exhausted. We should just spin a melodic line until it can be spun no farther; but on no account drama!’ ”(17) Wagner further planned “.. a return to the original form of the symphony, in one movement, with an andante middle section. After Beethoven no more four-movement symphonies are possible; everything in them seems to me just an imitation-- when a big scherzo is attempted, for instance.” (18) These unrealized, one-movement symphonies would have themes more cheerful and gemütlich than ones which tend to be associated with Wagner’s heavily-tragic output. As his wife Cosima noted in a diary entry on October 8, 1877: “In the evening he plays me a splendid theme for a symphony and says he has so many themes of this kind, they are always occurring to him, but he cannot use such merry things in Parsifal.”(19) On September 22, 1878, Wagner is found complaining that “when he has to compose Kundry, nothing comes into his head but cheerful themes for symphonies.” (20) From such information can be crafted a vague outline of what a middle- or late-period Wagner symphony might look like:

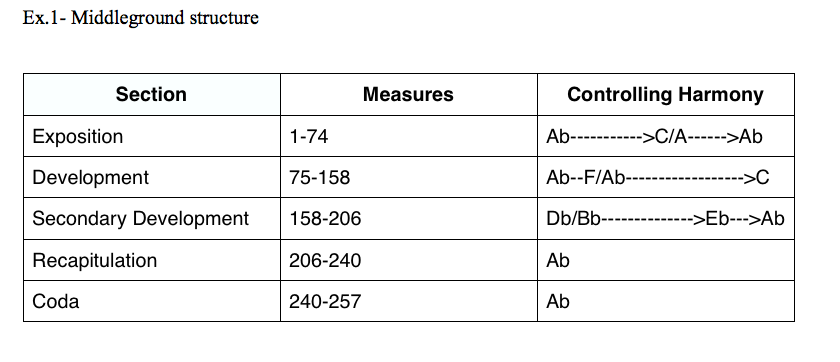

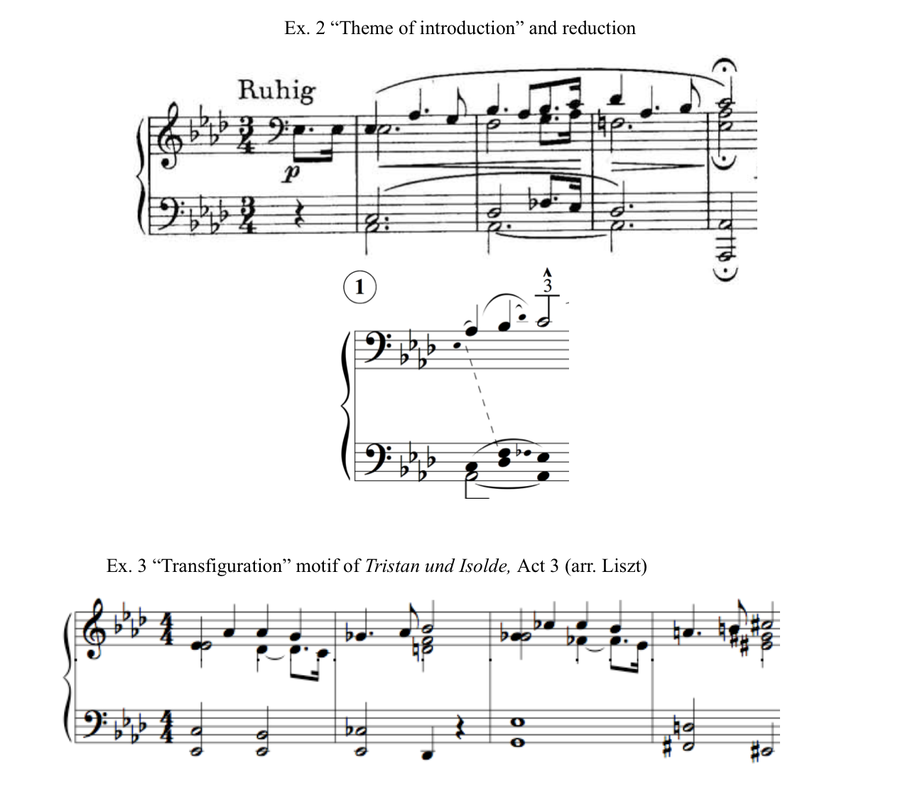

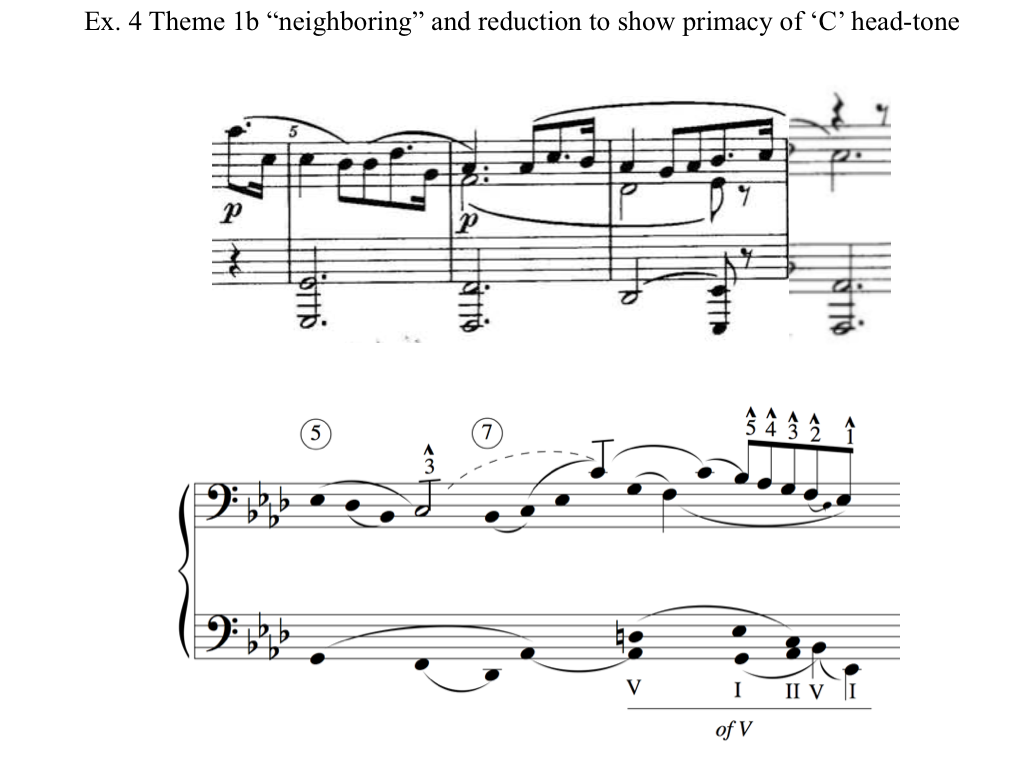

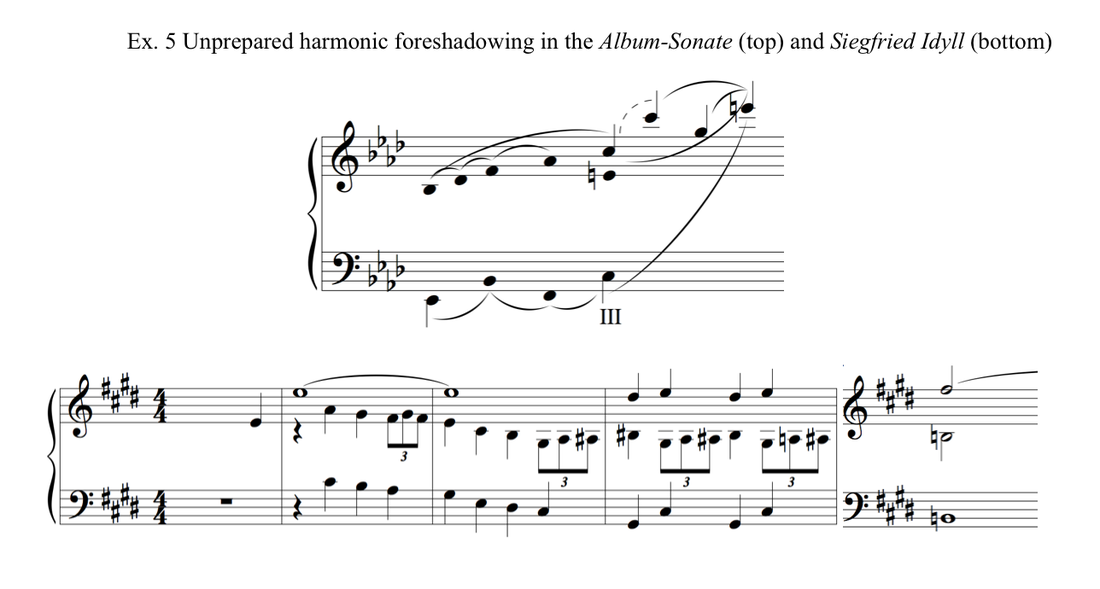

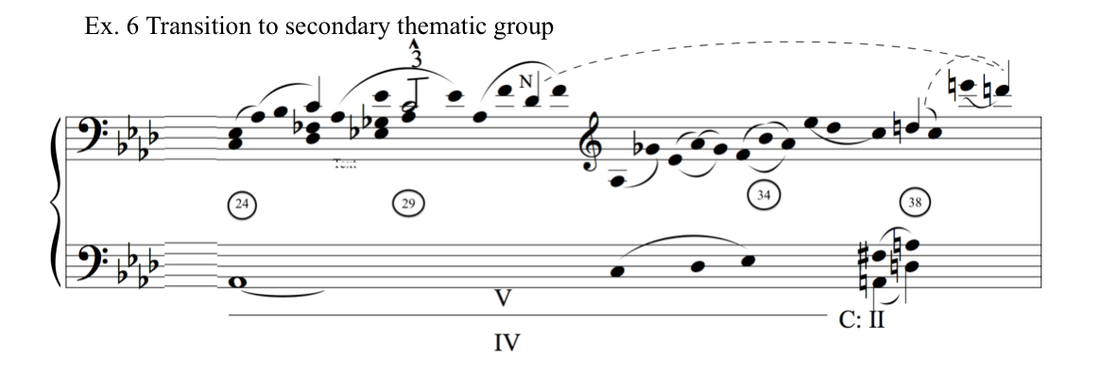

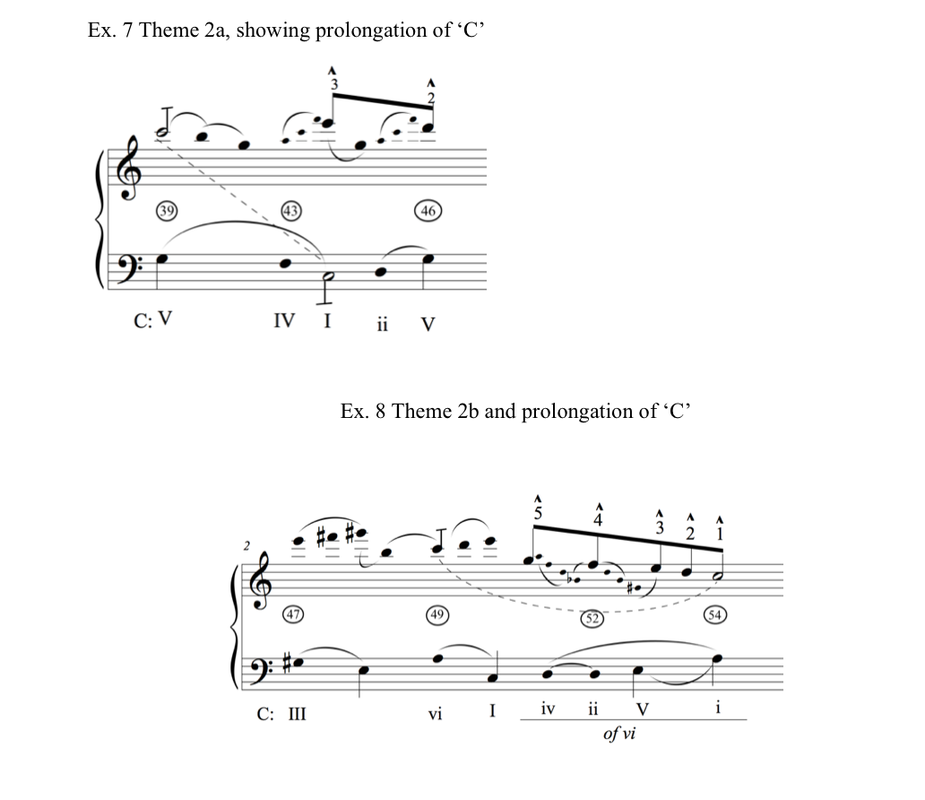

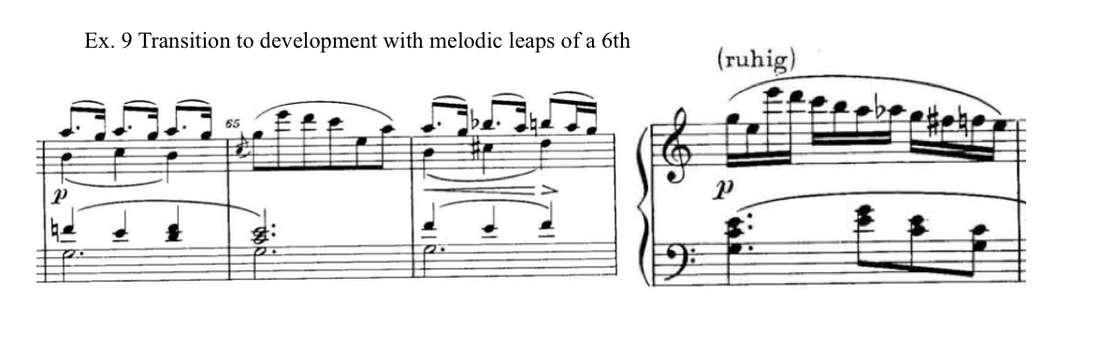

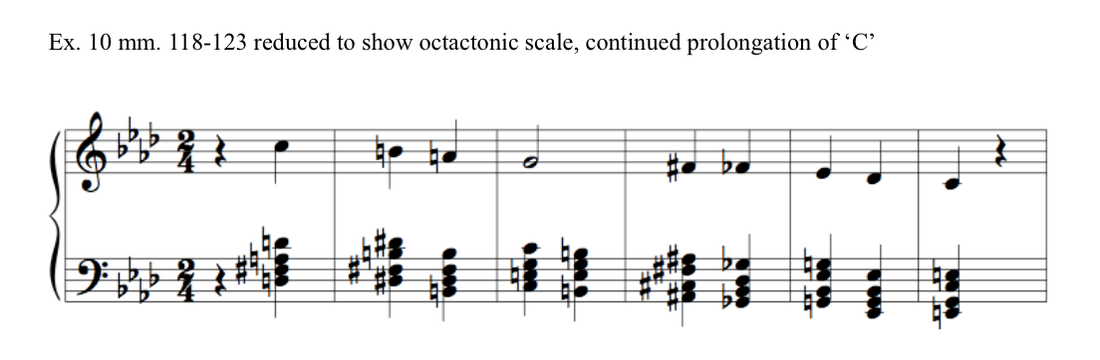

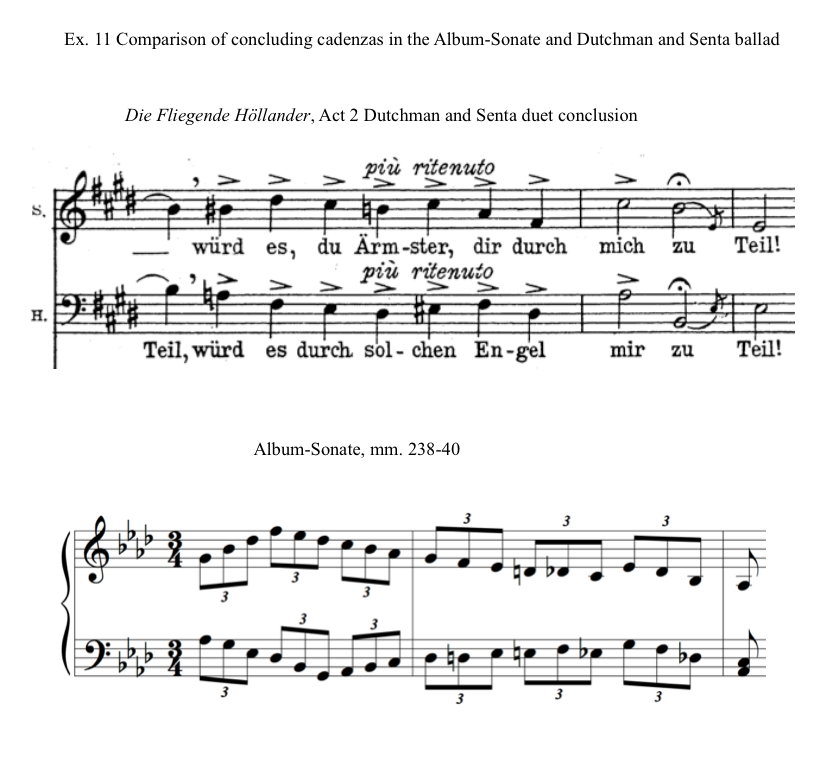

Textural Considerations Wagner eschews superfluous or virtuosic piano writing in favor of a texture which at all times supports the melodic-dialectical content of the sonata. As Dowd notes, “The work is completely lacking in the sort of virtuoso flourishes and cadenzas that one expects in most 19th century piano works.” While this statement helps describe Wagner’s approach to the instrument’s role in this work, its hyperbolic dismissal of formulaic cadential figures is somewhat misleading (as will be discussed later). Criticisms of the piano-writing in the sonata show a clear bias toward the virtuoso-vehicle which by this time had become standard fare; one interpretation of Wagner’s neglect in this respect is derived from statement from the composer himself that he had “never learned to play the piano properly,” (22) augmented by others’ opinion that “Undoubtedly his piano technique lacked polish and he was involved in too many things to spend the time with finger exercises, perfecting a proper technique.”(23) Of course, Wagner’s lack of technical expertise on a given instrument never prevented him from writing it the most diabolical of parts, and piano works from the composer’s youth show how clearly he had absorbed, for example, Beethoven’s approach to the instrument. (24) A Question of Form The Album-Sonate is ambiguous in its treatment of sonata form. The work has traditionally been seen as a sonata with chiastic elements, in that material from the second thematic group is recapitulated before that of the first.(25) Naturally, the rhetorical effect of such a recapitulation is weakened by the fact that it does not lend itself to a feeling the beginning restated; more importantly, the effect is further diluted by the second thematic group’s return in the subdominant key of D-flat. The defining elements of what qualifies a sonata as such are thus called into question. (26) As has been significantly noted (but not significantly taught in theory classes), crucial to sonata form is the fact that “The main feature that determines sections is harmonic in nature.” (27) Of course, the authors of such a quote are forced to concede to the multitude of contradictions which arise soon thereafter. Perhaps the most famous of these contradictions is the first movement of Mozart’s deceptively simple Sonata in C, k.545, in which the opening melodic material is brought back in the key of the subdominant, before an extended circular transition returns to the tonic in time for secondary thematic material. (28) Closer to Wagner’s own time is movement one of Schubert’s Op. 164/ D. 537, which also presents a subdominant return of the first theme. In such examples, it is despite harmonic implications that the recapitulations are genuine; in Wagner’s sonata, a reading of the subdominant return of the secondary thematic group is detrimental to a sense of large-scale structure and, more importantly, weakens the intuitive, natural satisfaction which follows the work’s harmonic/linear interruption and the subsequent tonic recapitulation of the first theme. As Charles Rosen notes, “The subdominant plays a special role in sonata style; it acts itself as a force for resolution, an anti-dominant...There even arose a kind of degenerate recapitulation, which began not in the tonic but in the subdominant, and which made a possible a literal reprise of the exposition, transposed down a fifth.” (29) In Wagner’s sonata, the thematic recapitulation in Db is closer to Rosen’s “Secondary Development,” prevalent in many late-eighteenth century sonatas and whose purpose is to lower the melodic and harmonic straining of the first, proper development. The author further points to the eighteenth-century theoretician Koch, who recognized the existence of such a section and required for it both the return of secondary thematic group material and a lack of cadence in the subdominant.(30) However, Rosen makes clear that a defining element of “anything that can be called sonata style” is the tonic resolution of the secondary thematic material: “The resolution of this material confirms the articulation of the exposition into stable and dissonant sections. A theme that has been played only at the dominant [in Wagner’s Sonata, at the mediant] is a structural dissonance, unresolved until it has been transposed to the tonic.”(31) As conservative as Wagner’s sonata is in harmonic and melodic exploration, its boldness lies in large-scale structure; its secondary themes are never resolved and yet its palindromic construction provides closure. The harmonic structural organization of the Album-Sonate is as follows: The first thematic group consists of two themes from which all the section’s melodic material is derived. It is the introductory theme (“1a”) which opens-- and thus closes-- the work, while theme 1b is the subject of development in the sonata’s primary development. Like the rest of the work, both themes are obsessed with the pitch ‘C’; the theme of introduction is concerned with its presentation via an initial ascent (see example 2 below), while theme 1b circles about the note. The relationship between theme 1a and that of Verklärung in Tristan und Isolde is one of transfiguration itself; in Tristan, however, the decisive agent of drama twists the melody into one which demands several modulations and increased expressiveness of harmony (compare with example 3 below). Here, the general ascent of the melody is intact, as are the 4th leaps and filled-in 3rds which are characteristic of the Sonate. Following a consequent phrase which presents a half-cadence (approached by the 5-zug shown above in example 4), Wagner takes the work down a foreshadowing road-to-nowhere, a interruption of the three phrases which make up theme 1b, constructed of diminution derived from the omnipresent dotted-eighth/sixteenth rhythmic motif, to an unprepared cadence in C major (m. 16, see reduced example below); the melody here reaches another C while the left hand begins ascending arpeggio/ ascending 6th which unifies the work and is to bring the work to a final close. This C major is both foreshadowing and affirming C—both the pitch and harmony—as head-tone and secondary key, as will be seen when the secondary thematic material is presented in C major. This foreshadowing method of revealing secondary tonal areas (both chromatic alterations of the mediant chord) in introductory material areas is used also in the second phrase of the Siegfried Idyll (mm.7-11) (see example 5 for a comparison of these allusions): In the Idyll, the role afforded to the brief G-sharp harmony will be greatly expanded, when the secondary tonal area of A-flat major is established later in the piece. In fact, in both of these works, Wagner uses a triad of the home key as a source his secondary tonal areas: in the Album-Sonate, the composer moves from A-flat to C to a pedal on E-flat before finally returning to A-flat, whereas in the Idyll his major tonal areas “arpeggiate” from E to G-sharp (A-flat) to C before returning to E.(32) At measure twenty a final, third “parallel” phrase closes the interrupted period and delivers a solid cadence in Ab. Measures 23-38 present more melodic diminution over a pedal pitch ‘Ab’; the harmony here is pointing directly to Db but a sudden semitone shift upward in the bass (m. 37) changes the direction violently, proving instead to be a II7 (V of V) in C (see example 6 in reduction below; the Db, so strongly hinted at for fourteen measures, will have to wait some time before being realized!). With the change of key signature and harmony at m. 39 to C major, the harmony pedals on V while three themes are introduced. The grouping of the first, 2a, deals with the same intervals-- the 4th and 6th-- which did 1a: while 1a begins with a leap of a 4th, followed by a stepwise ascent to ‘C,’ a 6th above the initial pitch ‘e-flat’; 2a begins with a scalar descent of a 4th (‘C’- ‘G’), followed by an ascending ‘G’-’E’ 6th in its contrasting phrase (mm. 42-44) before a half-cadence. Theme 2b (m.47), in all its distinctive appearances, is concerned with the transition to and tonicization of theme 2c (‘wie gesungen’ m.54) which appears atop a localized vi tonality before setting up a half-cadence transition at m. 64. This transitional material is a further exploration of the leap-of-a-6th motif which permeates this work (see example 9 below). It should be noted that throughout all of the second theme group, the key of C is never solidly established with a strong cadence; like the key of Db which was hinted at during the transition to the second theme group, an arrival in C will come only at the end of the long prolongation of that pitch during the development. However, the reductions provided below show how the pitch C is maintained in a prominent role throughout these sections. Like much else in Wagner, definite tonality is for the time avoided by his use of a deceptive cadence. As in the foreshadowing, arpeggiated cadence in the exposition (m. 16), the composer here again chooses a local III (in first position; the bass returns enharmonically to Ab) chord to set up the development (m.73). The descending 6th of theme 1b begins the development, with the harmony sliding through Eb minor (v) and Bb (II) before the transitional material from measure 12 sets up another cadence in C. This time, however, the harmony functions as a dominant of f-minor. Theme 1b occurs at small proportions of diminution and a 2/4 time signature (mm. 85-86; 92-93). The harmony of the development alternates largely between the two chords which best support the pitch ‘C’ which is insistently prolonged in the melody throughout this section, C minor and Ab. The phrases of this section begin with a melodic leap of a descending 6th; this is reflected with the countermelody in the bass which consistently leaps up a 6th (m.94, for example). The harmony shifts from this pattern at m. 118 (‘immer schneller’), at which point Wagner descends through something of an octatonic C scale (C-B-A-G-F#-F-flat-E-flat-D-flat-C; mm. 118-123) which serves to further highlight the preeminence of the note (see example 10 below). At 123, theme 1b is introduced again and sequenced until 130. At this point, the 6th leap is at its most stereotypically- Wagnerian, repeated again and again over diminished chords and arpeggios before the harmony finally matches the pitch which had dominated the development with a definitive cadence in C at 151. With C being firmly established, the key of Db is now given its proper due in this secondary development (m.158). From the ‘G’-’A-flat’-’C’ flourish which festoons this cadence emerges the second phrase of theme 2b, with chorale-like part-writing and fermati; this is met with a the theme’s first phrase. The order of events is now corrected, and the themes are presented in the manner in which they occurred in the second theme group. A subdued snippet of theme 1b is interspersed with an increasingly energetic wie gesungen theme (2c), the texture of which recalls that of the development (mm. 172-184). A dominant pedal in a localized E-flat harmony persists from 185, interrupted by one last appassionata iteration of the wie gesungen theme at 191. The harmony is brought back for the last time to C at 199, the mediant here finally appearing in its natural and resolved minor mode. It is after this resolution that the harmonic interruption occurs with a dominant in the home key of A-flat (mm. 201- 205). The work begins anew with the harmonic recapitulation and the theme of introduction (1a) at m. 206; this theme is answered by itself, inverted, in measure 210-211. Measures 212-213 represent the whole action of the sonata in three melodic notes and two harmonies: the rising third in the melody over the two defining chords of the development (F minor and C major) is a tongue-in-cheek reflection on the harmonic turbulence which preceded it. The inverted variant of 1a is repeated and sequenced again in 214-216, and most colorfully in 222-25. The theme returns to its natural state in 230 and culminates with a duet-cadenza which sounds as though it were written twenty years earlier. As a point of comparison, included here will also be the cadenza from the Dutchman and Senta’s duet from Act 2 of Die Fliegende Holländer (see example 11 below). This conclusion is telling and illustrates just how disparately Wagner saw his instrumental music from his dramatic music. Regarding such melismatic pleasantries, Wagner writes in A Communication to my Friends (1851):

“How very gradually this came about [changes in melodic treatment of text], however, as waned the influence of accustomed operatic melody, will be obvious from a consideration of my music to the Flying Dutchman. Here I was still so governed by the wonted Melismus, that I even retained the Cadenza, here and there, in all its nakedness; and to any one who, on the other hand, must admit that with this Flying Dutchman I commenced my new departure in the matter of melody, this may serve as proof with how little premeditation I swerved into that path-- In the further evolution of my melody, however un-deliberately I followed it in Tannhauser and Lohengrin, at all events I freed myself more and more definitely from that influence...”(33) From 240 there is a coda which unites the outer phrases of 1b which were separated by a third phrase of half-cadence in mm. 11-12. The work ends with the same arpeggio with which C major was first introduced in measure 16, now resolved to A-flat and concluding with the 6th-leap corrected to ‘E-flat’-’C’. Conclusion “I tell him I should like to hear the sonata which Frau W. had. ‘It is nothing much,’ he says, ‘for I wrote it for her, and always, when I sit down to do something, it turns out miserably.’ “ “He plays me the sonata for Math[ilde] W. and laughs heartily at its ‘triviality’, as he calls it. He says he has never been able to write an occasional piece-- this sonata is shallow, nondescript..” Wagner’s remarks to his wife Cosima here come from September 1871 and January 1878, an entire generation after the composition of the Album-Sonate. The composer’s opinion of the work, however, cannot obscure the fact that it shares a large deal in common with his greatest works; the clearest and most impressive of these is the attention paid to its unifying detail. It shares more with Wagner’s late-period instrumental masterpiece, the Siegfried-Idyll, for which many of the characteristics described by the composer mentioned above also apply. The Album-Sonate is a work which, Wagner would say, is nothing more than payment for a lovely sofa cushion given to him by Mathilde Wesendonck; as in the musical settings of Wesendonck’s lackluster poetry in the Wesendonck Lieder, Wagner’s music here also transcends its aim of intention. The Album-Sonate fittingly rounds out the Wesendonck repertoire, joining the likes of Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Tristan und Isolde, and the lieder as music inspired in one way or another by the presence of that woman in Wagner’s life. The Album-Sonate may have been an occasional piece, but here the occasion was certainly more than just payment for a piece of furniture. Notes 1. “Do you know what will happen?” 2. Quoted in William S. Newman. “Wagner’s Sonatas”. Studies in Romanticism. 7 (1968). p.136 3.. Wagner described the change himself: “ From here [the Flying Dutchman] begins my career as poet, and my farewell to the mere concoctor of opera-texts. And yet I took no sudden leap. In no wise was I influenced by reflection; for reflection comes only form the mental combination of existing models...My course was new; it was bidden me by my inner mood.” William Ashton Ellis, trans. Richard Wagner’s Prose Works vol. 1 London: Kegan Paul, Trübner & Co., Ltd. 1892. p.308. A composer disavowing earlier works is by no means uncommon; nor are the instances in which those earlier works are revealed to be representative (in their own way) to subsequent listeners-- perhaps the analysis community has been too quick in rushing to Wagner’s judgment here! 4. Cosima Wagner’s Diaries, trans Geoffrey Skelton (New York, 1977). Entry of February 14, 1876. 5. Some Americans might have rather accepted Wagner’s inscription upon these sketches--“Wishing I were American! (“Amerikanisch sein wollend!”) rather than the ill-received March. 6. As Robert Bailey has pointed out, this prologue was added to Götterdämmerung in January of 1849, but was subjected to a thorough revision; the version of the scene with which we are familiar was finished on December 15, 1852. Bailey, Robert. “The Structure of the Ring and its Evolution.” 19th-Century Music, 1 (1977), pp. 48-61 7. William S. Newman, p. 136. With the the text of Götterdämmerung in place as of late 1852, we can at least know the answer to the question when it comes from the Norns: the ending of the age of Gods. With Wagner’s own metaphorical attempt at such in Dresden having been a massive failure, perhaps we may add to such speculation over an initially programmatic title for the Sonata. 8. John Andrew Dowd. “The Album-Sonata for Matilde Wesendonck: A Neglected Masterpiece of Richard Wagner”. The Journal of the American Liszt Society. 10 (1981). p. 43 9. William S. Newman. p.130 10. D.A. Conflenti (1975). Periodicity in the Programming of Solo Piano Music in New York Recitals, 1968-1973: An Essay Together with a Comprehensive Project in Piano Performance. (Order No. 7613373, The University of Iowa). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, p.120. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/302763202?accountid=14749. (302763202). Though nearly forty years old, the relevance of this research has changed little, with the five most-popular composers represented on piano recitals being Chopin, Liszt, Brahms, Schubert, and Schumann. The study found no performances of Wagner’s piano music. 11. Despite his later disavowal of the work, Wagner’s opinion of the Album-Sonate shines through in his statement that it is his “first composition since the completion of Lohengrin (6 years ago!)” despite having written a playful Polka shortly prior to the sonata. Statement comes from a June 20, 1853 letter to Otto Wesendonck, quoted in William S. Newman. p.136 12. See William S. Newman. p. 130.The two sonatas-- both single-movement works-- were composed within three months of each other. Wagner did not hear Liszt’s sonata until 1855, while Liszt was unaware of Wagner’s sonata at least until July 1853-- five months after the February 2, 1853 completion date of his own. 13. Quoted in Patrick McCreless, “The Musical Structure of Siegfried” in Wagner's Siegfried: Its Drama, Its History, and Its Music. UMI Research Press. 1982. pp. 93-94. 14. From Wagner’s ‘Brown Diary’; quoted in Carolyn Abbate. “ Wagner: ‘On Modulation’, and ‘Tristan’ “. Cambridge Opera Journal, 1:1 (Mar., 1989), pp. 35-58. 15.Ernest Newman. The Life of Richard Wagner, vol. 4: 1866-1883. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1946. p. 615 16.Cosima Wagner’s Diaries, trans Geoffrey Skelton (New York, 1977). Entry of September 22, 1878 17.Ibid., entry of December 17, 1882 18. Quoted in Newman, Ernest, p. 605 19. Cosima Wagner’s Diaries. Entry of October 8 ,1877 20.Ibid., entry of September 22, 1878 21. For an excellent consideration of Wagner’s application of theoretical ideals to his dramatic works, see Warren Darcy. Wagner’s Das Rheingold. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press. 1993 22. Wagner’s Prose, vol. 1 p.4 23. Dowd, p.43 24. For example, note William S. Newman p. 135 on the Grosse Sonate in A :“The ideas and styles of both the introduction and the fugue, for example, recall those in the finale of Beethoven’s Opus 101 in A, whereas those of the first two movements recall passages in the first movement of the “Eroica Symphony” and the slow movement of Opus 106 in B-flat, respectively.” 25.Dowd’s measure numbers 26. The form is found in Wagner’s dramatic works as well; see the Prelude to Act 1 of Die Meistersinger for another sonata with similar formal considerations. The Prelude to the third act of the same music-drama provides further insight into Wagner’s treatment of chiastic form. 27.Allen Forte and Steven E. Gilbert. “Sonata Form and Structural Levels” in An Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis. New York: Norton. 1982. p.277 28. Ibid., p.279: “This example also illustrates an exception to the general harmonic design of the sonata form, since the reprise begins with the subdominant harmony rather than with the tonic.” 29. Charles Rosen. Sonata Forms. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. 1988. p.288. 30. Ibid., p.289. 31. Ibid., p.287 32. The augmented triad plays an even more significant role in the structure of the Idyll. See Cartwright, Mark Anson. Chord as Motive: The Augmented-Triad Matrix in Wagner’s ‘Siegfried Idyll’ ”. Music Analysis, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Mar., 1996), pp. 57-71. 33. Ellis vol. 1, p. 373.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

August 2023

AuthorYouTube |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed